Nina Simone : La Voix d'un Peuple

Lisez les notes de la pochette de notre édition exclusive de Nina Simone Sings The Blues

“Le blues avait le pouls des gens qui continuent d’avancer.” – Langston Hughes

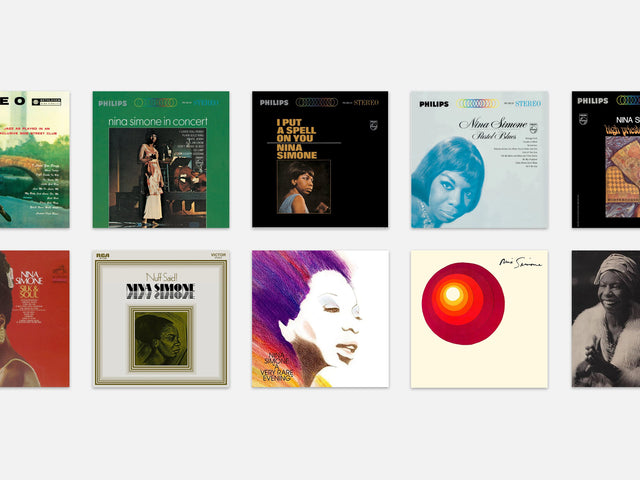

Sitting at RCA studios to record Nina Simone Sings The Blues in December 1966 and January 1967, Simone was in her prime. Unlike her previous albums with the smaller labels of Bethlehem Records, Colpix, and Phillips, RCA’s size and its signature artist Harry Belafonte meant that Simone’s music and message would reach her biggest, most diverse audience to date.

Produced by Danny Davis, an A&R executive with whom Simone was working for the first time, Sings The Blues was billed as Simone’s first concept album. Seeking to recreate the intimate setting of her live shows, Davis gathered an elite group of New York artists: guitarist Eric Gale, drummer Bernard Purdie, organ player Ernie Hayes, bassist Bob Bushnell, harmonica and sax player Buddy Lucas, and Simone’s frequent guitarist Rudy Stevenson. Part juke joint, part jazz club, part Harlem salon, Sings The Blues showcased Simone at her best – making pop political and protest sultry.

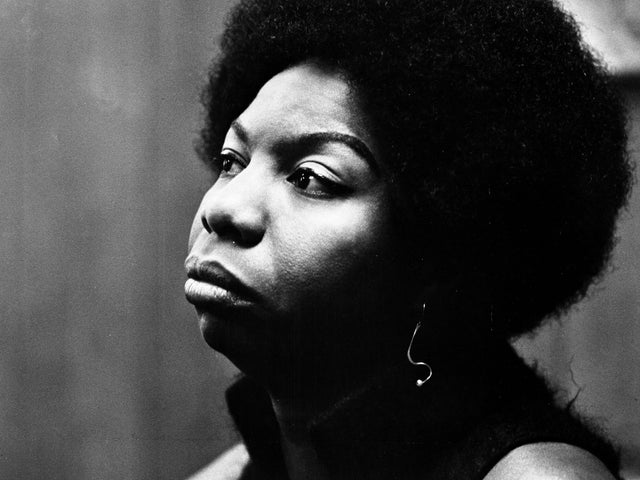

But, she wasn’t always this way. Born Eunice Waymon in 1933, Simone grew up in segregated Tryon, N.C. At 3, she was playing her mother’s favorite gospel hymns for their church choir on piano; and by 8, her talents garnered her so much attention that her mother’s white employer offered to pay for her classical music lessons for a year. Determined to become a premier classical pianist, Simone trained at Juilliard for a year, then sought and was denied admission to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia — a heartbreaking rejection that led to a series of reinventions — renaming herself Nina Simone, performing in Atlantic City nightclubs and adopting jazz standards in her repertoire.

She would go on to have her only Top 40 hit with “I Loves You, Porgy” from the opera Porgy and Bess in 1959 off her debut album, Little Girl Blue. To further her music career, Simone moved back to New York, where she became part of a cohort of socially committed artists, joined the civil rights movement, and garnered fame for her protest anthem, “Mississippi Goddam,” a song she composed in response to the assassination of the civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Mississippi and the murder of four African-American girls in a church bombing in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963.

In her late career, Simone reflected, "I hope the day comes when I will be able to sing more love songs, when the need is not quite so urgent to sing protest songs. But for now, I don't mind." And though this tension haunted Simone’s career, *Sings The Blues *has no such struggle. In contrast, all Simone’s earlier albums, including The High Priestess of Soul, which Phillips Records expeditiously released a few weeks before this album, were an eclectic mix of protest, jazz, folk, gospel, and R&B songs. Davis encouraged Simone to find a musical theme, making Sings The Blues her most unified album. Unlike her male contemporaries, like Bob Dylan or the Beatles who sought the mythic music of African American bluesman Robert Johnson, Simone found inspiration in the seductive, empowered style of Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, the oft-forgotten blueswomen who reigned American popular music in the 1920s.

Simone takes charge on “Do I Move You?” and “In The Dark,” her dusky voice transporting us to a forbidden boudoir, a private dance club, or both. On songs that typically invoke loss and lament, such as Buddy Johnson’s standard “Since I Fell For You,” Simone revels in lust. “Buck,” a song written by her husband and manager Andrew Stroud, gives us Simone’s penultimate cheekiness. But, it is her sly phrasing and slow pacing throughout “I Want A Little Sugar In My Bowl” that she made both timeless and novel, conjuring up the blueswomen of old while capturing the energy of a new generation of American women on the verge of sexual liberation.

But, in Simone’s hands even the blues were up for grabs.

On the gospel infused “Real Real” Simone converges traditions, bringing to mind the jazz critic Albert Murray’s adage that the same person playing in the blues club on Saturday night played the same chords in church on Sunday morning. “The House Of The Rising Sun,” the folk song that she first recorded for the 1962 Colpix Records album At The Village Gate, is far more boisterous and bolder than her original version, reflecting how Simone’s musical and political confidence had undergone a dramatic transformation within a few short years.

On “My Man’s Gone Now,” Simone unexpectedly revisits Porgy and Bess, and produces one of the album’s most riveting moments. It was so mesmerizing that Davis felt compelled to write on the album’s original notes: “Miss Simone was physically and emotionally exhausted from previous recording, but she sat down at the piano and began to play and sing this moving ‘Porgy and Bess’ tune . . . From somewhere she summoned the stamina to deliver with even more intensity and a spirit a rare, perfect performance that could not be improved.”

But, outside the studio doors, the nation was on fire. Two months before she began recording, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party in Oakland; two months after the album’s release, race riots broke out Buffalo, Detroit, and Newark. Simone adjusted her politics, like her sound, to the times and songs like “Blues For Mama” and “Backlash Blues” bridged the various social movements – Women’s Liberation, Black Power, and the Anti-War Movement of the late 1960s – with which Simone sympathized.

Co-written with jazz vocalist and activist Abbey Lincoln, “Blues For Mama” was one of the era’s only songs to mention, much less prioritize the point-of-view of female victims of domestic violence over that of their male abusers. The song’s explicit repudiation of and clear revision of the more ambivalent representations of domestic violence in the early blues songs such as Rainey’s “Sweet Rough Man,” Smith’s “T’Aint Nobody’s Business,” and even Billie Holiday’s jazz standard “My Man,” put this tune ahead of its time and should be revered as much for its funky sound as its vanguard feminist message.

Simone’s most playful and poignant rebuke was “Backlash Blues,” a poem given to her by writer Langston Hughes. Penned in 1967, Hughes’s lyrics lambasted ongoing American racism and the government’s disproportionate drafting of young African American men to fight in Vietnam. Keeping the standard 12-bar blues verse of Hughes’s original, Simone adds a fierce shuffle rhythm – reminiscent of but played at a much slower tempo than the typical boogie-woogie shuffle.

Simone’s protest is the loudest, however, when she actually rewrites Hughes’s lines. In the poem, Hughes waits until the end to reverse course and give the blues back to the government, racists, and old "Mister Backlash." Simone, on the other end, turns that revenge into a refrain, ending each chorus singing, “Mister Backlash, I’m gonna leave you with the backlash blues.” Here, the blues becomes its own form of racial justice, imbued with more power with each shout.

To listen to Sings The Blues is to hear an artist and a nation on the precipice. Not yet jaded by the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the FBI’s repression of the Panthers, or the conservative rise of Richard Nixon, Simone aligns her blues to the possibility of change. Tied to one genre, Simone gives breadth. Passionate, urgent, and liberatory, Simone takes our blues away, while bringing herself and the rest of us closer and closer to her ever so elusive goal to be free.

Salamishah Tillet est professeur associé d'anglais et d'études africaines à l'Université de Pennsylvanie et membre de la faculté du Alice Paul Center for Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies. Elle est également cofondatrice de A Long Walk Home, une organisation à but non lucratif qui utilise l'art pour éduquer, engager et autonomiser les jeunes afin de mettre fin à la violence contre les filles et les femmes.

Rejoindre le club!

Rejoignez-nous maintenant, à partir de 44 $15 % de réduction exclusive pour les enseignants, les étudiants, les membres des forces armées, les professionnels de la santé & les premiers intervenants - Faites-vous vérifier !