Los 10 mejores álbumes de James Brown que debes tener en vinilo

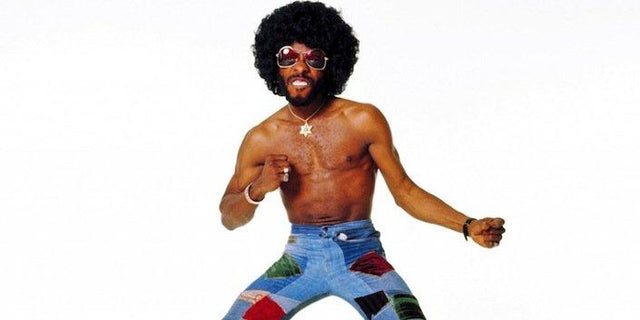

James Brown was not an albums artist.

That's a bad sales pitch. We're here to talk about Brown's best albums, after all. But any statement to the contrary would be a lie. Brown released nearly 70 albums and most of those came between 1959 and 1976. That's an ungodly number, made a little bit less impressive by the fact that Brown surrounded the wheat of his singles with a hell of a lot of chaff.

Most of his albums feature a few undeniable singles surrounded by tons of re-released, re-recorded or unoriginal material to make one whole long-player. For people who want to avoid this side of Brown's discography, there are a few box sets—shouts to 1991's truly incredible 4-CD collection Star Time—that serve as an overview of his career.

But paring down Brown's career to the indispensable highlights misses something essential about the accurately self-styled "Hardest Working Man In Show Business." More than anything, Brown was a striver.

Nobody in the history of American music has ever tried harder to entertain a crowd. Every James Brown slab comes coated in a dried layer of flop sweat. To listen to Brown is to hear a man who danced his ass off in Chitlin Circuit juke joints and theaters where air-conditioning was a far-away dream. It's taking in the vocal-chord shredding screams and raw physicality that helped birth the body-movingest genre this country's ever known. It's trying to reckon with a man so crazed by the idea of putting on a good show that he'd dance himself into a stupor, collapse in a puddle and then put on a cape.

That workhorse mindset is exactly the sort of thing that gave us so much material to work with. Anyone who wanted James Brown was probably going to get more of him than they could handle. The man didn't know how to pull back, how to give anything less than too much.

And that can be daunting for anyone digging through crates packed too tight with Brown releases, as overwhelming as Brown himself. It's not the sort of feeling you want creeping in if you're just looking for something to move an ass or two.

That's why we've put together these 10 titles, distilling Brown down to his most essential cuts without losing the shagginess and humanity that make Mr. Dynamite so impressive in the first place. Godly feats are only worthy of praise when they’re performed by a person, after all. And as Brown will remind you time and time again, he’s all man.

Live At The Apollo

Of course, we start here. Brown was a performer first and Live at the Apollo is the best representation of that fact. If you want to cut this list down to one release, Apollo would be it.

Even this early on in his career, Brown knew that performing was his bread and butter. That's why he financed the recording of this 1963 release with his original band The Famous Flames out of his own pocket. Even after outlying the cost, Brown had to strong-arm the label into releasing it. They didn't think an album of already released songs recorded live could turn a profit. They didn't get it.

The audience—both inside the historic Harlem theater and in record stores around the country—knew better than the suits at King. You can hear it in the frantic screams that cut through the tantalizing performance of "Lost Someone" and the reactions to Bobby Byrd and Co.'s pristine, lockstep takes on hits like "Try Me" and "Please Please Me." You can see it in the chart performance of the album, which sold more than a million copies and nearly topped the pop charts.

And small wonder. Apollo is so unbelievably vital that it can be credited with birthing a wholly separate genre, one of the few that Brown never dabbled in. The proto-punkers in MC5 credit the release with inspiring their own "gut level" performances on the seminal Kick Out The Jams.

The Payback

Where Brown's early releases had relied on his white-hot energy, this scrapped soundtrack for the blaxploitation vigilante flick Hell Up In Harlem is cold as a mother. And we all know that's the best way to serve up revenge.

The title track contains some of the most out-there exultations of Brown's entire career, but the groove is too nice to let folks linger on them. Only a showman of the Godfather's caliber could sell a line like "I don't know karate, but I know cuh-razy!"

Brown's decision to slow it down and shuffle a bit practically invented funk and The Payback is Brown fully embodying the sound he helped create. Living room listeners and back-alley lowlifes can't help but be awed.

Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)

Given that you can draw a line between Brown and just about every important artist and musical movement to come after him, it's almost unnecessary to point out that the music he made contained multitudes. He could do it all and did, frequently within the confines of the same half-hour long album.

Even knowing that, it can be hard to jibe the revolutionary zeal of this album's title track with the songs that come after it. Brown kicks off the album by dropping an anthem for the entire Black Power movement and just over 10 minutes later, he's singing "Mama, come here quick, and bring me that licking stick" over Jimmy Nolen's trademark chicken scratch.

But even Brown's less fleshed-out songs and slow-burning covers like "Let Them Talk" managed to reach out their tendrils and find important folks to inspire. The politics and sounds of Say It Loud were a huge influence on Bob Marley and the Wailers, who even went so far as to cover the song "I Guess I'll Have To Cry Cry Cry."

Soul On Top

Soul On Top is a flex, an album that finds Brown walking right up to the borderline of wondering if he could and thinking if he should. But right at the moment when the Soul Brother No. 1 is about to cross over into a failed genre experiment, Brown smartly jumps back and kisses himself.

A soul-funk-jazz fusion played by a big band with James' raw-as-hell vocals laid over the top shouldn't work at all. In some cases it doesn't, like the horn-drenched cover of Hank Williams' country standard "Your Cheatin' Heart."

But one listen to the big and brassy take "It's A Man's, Man's, Man's World" shows that Brown at the peak of his soul era could only stumble. His momentum was such that he'd never truly fall.

Hell

It would be understandable if 1974's Hell was mostly filler or clunkers, close as it is to a through-and-through classic like The Payback. But outside of "When The Saints Go Marchin' In"—possibly one of the worst tracks of Brown's career and nearly a parody of Brown's cold and funky early ’70s sound—Hell is incredibly solid. The funkified remake of "Lost Someone" is a worthy update on one of Brown's most famous songs. And Fred Wesley and the rest of J.B.'s ensure that "Papa Don't Take No Mess" is the fastest 14 minutes you'll ever hear.

Sex Machine

Brown was a hell of an artist, a singular entity when viewed through the lens of history. But down on the granular level, in his element, the way that people must have viewed him in his time, Brown was a bandleader.

The screeching soulster of his early years is nothing without Bobby Byrd and the rest of The Famous Flames. And James Brown’s funk wouldn’t happen without the world-class musicians in the J.B.s. Sex Machine is one of the best examples of the group’s power laid to tape. The pseudo-live album (many of the tracks are studio recordings with reverb effects laid of the top) is a document of the overwhelming power of a band that contains Maceo Parker, Clyde Stubblefield, The Collinses and Bobby Byrd.

Real heads are sweating just reading that sentence and they live up to their legendary stature here with extended jams on classics like the title cut and “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose.”

Think

Even before he was radically reshaping American music in his image, Brown was an innovator. The Chitlin Circuit audiences who heard him turn The 5 Royales “Think” on its head got an early taste of the outside-the-box thinking that Brown and his Flames were capable of.

Though it can be hard to remember, in the wake of later successes, there’s a reason that Brown started off his Apollo set with “I’ll Go Crazy.” Here it’s proof that Brown had swagger even when he was down on his knees.

Love Power Peace, Live At The Olympia, Paris 1971

If Apollo was the perfect capturing of Brown at the high-point of his rock and boogie years, this Paris concert is a necessary capturing of one of the greatest funk bands to ever walk the planet.

It’s the only truly live recording with the J.B.’s and even if it took decades to make it out of the vault—the 1971 recording languished until 1992 because the band member’s left to form a little band called Parliament-Funkadelic—it needs to be on your shelf.

Cold Sweat

It can be hard to understand how weird “Cold Sweat” was in its time.

The seven-minute proto-funk cut from the album of the same name had the same impact that Prince’s “When Doves Cry” would decades later. “Cold Sweat” comes loaded down with the sound of thousands of musicians saying “Oh, I didn’t know you could do that.”

Perhaps the best way to realize what an odd track “Sweat” is is to listen to the rest of the album that it hails from. Cold Sweat is full of covers of tracks that accurately represent the world that Brown was dropping a funkified bomb on. Covers of nightclub standards like “Fever” and “Stagger Lee” sound downright prehistoric compared to what Brown lays down in the album opener.

Hot Pants

The title track is going to get all the love, but the playground “nanana” guitar on the equally trouser-obsessed “Blues And Pants” is an unsung high of Brown’s funk period. Almost all of the songs on this album spread out toward the 10-minute mark, showcasing a band that could play for days straight and often did.

Únete al Club!

Únete ahora, desde 44 $15% de descuento exclusivo para profesores, estudiantes, miembros militares, profesionales de salud y primeros respondedores - ¡Verifícate!