通过冒险选择一位相对无名的蓝调歌手穆迪·沃特斯,菲尔和伦纳德·切斯可能无意中发明了摇滚乐。在收购了一个独立唱片公司阿里斯托克拉特唱片后,切斯兄弟——生活在芝加哥南区的波兰移民——印了3,000张沃特斯的单曲《我不能满足》。这首歌成了热门,沃特斯在兄弟们重塑的切斯唱片上的后续发行为像滚石乐队、吉米·亨德里克斯和甲壳虫乐队这样的音乐人铺平了道路,使蓝调音乐融入的摇滚乐成为全球现象。

Of course, the invention of rock ’n’ roll cannot be traced exclusively back to Waters and Chess. Fats Domino, Little Richard and Elvis Presley—artists associated with Imperial, Specialty and Sun Records, respectively—have all been credited as forefathers of the genre. But even though other artists and independent labels released similar sounds around the same time, Chess Records had a profound effect on the musical revolution of the mid-20th century.

Aside from Muddy Waters, Chess’ biggest star was another rock ’n’ roll innovator: Chuck Berry. Berry recorded early hits like “Maybellene” and “Roll Over Beethoven” with Chess, propelling both the label and his own unique style to the forefront of public consciousness. Although Berry left the label for much of the 1960s, he remained indebted to the Chess brothers for kick-starting his career. When he returned to Chess Records in 1970, he titled his next album Back Home.

The Chess brothers’ timing happened to be perfect. Black Americans fleeing the Jim Crow-era South had been settling in Chicago, resulting in both an influx of talented musicians and an audience eager for blues music. Around the same time, white listeners nationwide were growing increasingly interested in consuming black music. Chess Records, either intentionally or not, helped bridge the gap between the segregated sides of a country still politically split along geographic lines. The Chess brothers weren’t alone in their pursuit, and not all of the label’s releases became classics, but the strength of their catalogue remains unparalleled.

In its early years, Chess Records, like most labels at the time, was known for putting out these types of 7-inch records. Most albums contained two singles, an A side and a B side. Chess didn’t even release an LP until 1956, six years after the label’s formation. That first LP was the soundtrack to a relatively obscure film called Rock, Rock, Rock, and featured songs by Chess artists Chuck Berry, the Moonglows and the Flamingos.

Many of Chess’ subsequent LPs were actually “best of” collections of singles the label had previously released. Chess would combine well-known Chuck Berry hits, for instance, and organize them into one package. The practice was far from the way albums are created today, and individual artists had little say in the cohesive vision of the finished product. As the LP became a standard across the music industry, however, Chess adapted and began releasing longer albums rather than focusing on singles.

Below is a list of 10 such Chess LPs that are worth owning on vinyl. Although the Chess brothers splintered their business off into three subsidiaries—Checker, Argo and Cadet—this list focuses on LPs released on the Chess imprint.

Muddy Waters: Fathers & Sons

Unlike a few of Muddy Waters’ other Chess LPs, there’s nothing experimental about Fathers & Sons. The songs don’t take many risks. The musicians don’t rely on gimmicks. It’s a straightforward blues album, but it’s both Waters’ and Chess’ best.

The album carries a persistent energy from its opening track, “All Aboard,” as if Muddy is literally welcoming listeners on board a 14-track journey through his blues. To encapsulate the upbeat nature of the studio records, Fathers & Sons was released as a double LP. The second album consisted of live recordings of Waters’ performances.

The quality of those recordings are strong for the time, especially considering Chess’ history of releasing “live” music. The label’s 1963 release Chuck Berry On Stage was marketed as a live album, but featured mostly previously recorded tracks with overdubbed noises of audiences cheering and clapping. On Fathers & Sons, it’s easy to detect the chemistry between Waters and his band as they jam for various real crowds.

The recording quality of the LP's studio sessions is similarly strong. The drums are light and tinny, allowing Waters’ rich voice and searing electric guitar to cut through to the center. The album features a notable cast of fledgling blues players in supporting roles, all of whom get at least a moment in the spotlight. Paul Butterfield plays harp, blowing from the opening of “All Aboard” through the closing of “I Feel So Good.” Otis Spann and Booker T and The M.G.’s Donald “Duck” Dunn also play on the album. Spann aside, many of the album’s young session players were white, symbolizing the expanding reach of the blues. It’s a masterclass in blues at the highest level, taught by the master himself.

You can get the Vinyl Me, Please edition of this album over here.

Chuck Berry: St. Louis to Liverpool

St. Louis to Liverpool is one of the aforementioned “best of” collections that Chess released in an effort to capitalize off the growing success of LP records. As a result, the album contains a bevy of catchy singles that even the most casual modern listener might recognize, like “Little Marie” and “No Particular Place to Go.” The album, released in 1964 shortly after Berry served a stint in prison, displays the peak of the talent he possessed in his early career.

There are shades of the classic-rock sound bands like the Beatles would come to define in the music, and the album serves as a reminder of Berry’s undeniable influence on that entire generation. Even the title of the LP is a nod to how far Berry, born in Missouri, had sonically traveled.

But the songs on St. Louis to Liverpool also represent Berry’s standalone power as an artist. He shouldn’t just be remembered for leading the world to the Beatles; he should be compared alongside them. His career might not have evolved as dynamically as the Fab Four, but “You Never Can Tell” is at least as enjoyable as “Please Please Me.”

Berry’s guitar playing throughout St. Louis to Liverpool is raw and frenetic, his singing smooth and sweet. The album might not flow together as seamlessly as Sgt. Peppers or the Beatles’ other later releases, but almost every song is as timeless as the best rock ’n’ roll records. The album is a classic in every sense of the word, and truly does represent the “best of” what Berry had to offer.

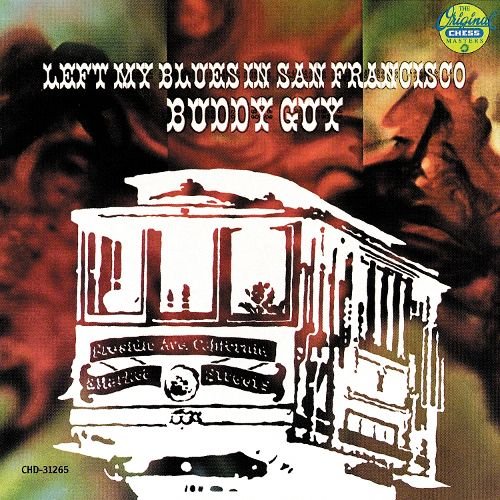

Buddy Guy: I Left My Blues In San Francisco

Buddy Guy is one of the last living members of the Chess heyday still performing, primarily at his own appropriately named Chicago club, Legends. Guy is a legend himself, a guitar virtuoso with a husky, unforgettable voice capable of conveying deep layers of emotion. Guy began his career as a studio session player at Chess Records, appearing as a credited guitarist on several Muddy Waters records.

Guy’s debut studio LP, I Left My Blues In San Francisco, is also the only record he ever released on Chess as a solo artist. Guy reportedly butted heads with the Chess brothers during his time at the label, claiming they limited his creative freedom. Even if Guy was unable to fully be himself in the studio, this album is still rife with the kind of artful expression that would define him for the decades to follow. His yelping and shaky, wavering voice on a song called “I Suffer With The Blues” should have been the only evidence the Chess brothers needed to know Guy had a special sense of the blues within him.

You can get the Vinyl Me, Please brand-new reissue of this album right here.

Muddy Waters: Folk Singer

Fathers & Sons is Muddy Waters’ best album because it encompasses everything great about his signature sound, but Folk Singer is the purest distillation of his musicality, as well as a demonstration of his versatility. The LP, released in 1964 as an attempt to cater to fans of the folk music revival of the time, finds Waters trading his electric guitar for an acoustic. He’s backed by Buddy Guy, as well as Willie Dixon on bass and a supporting cast of Waters regulars.

Although Waters’ music defined the Chicago blues sound, Folk Singer finds him pontificating a return to the South. The album opens with “My Home Is In The Delta,” where Waters punctuates a line about leaving Chicago with “I sure do hate to go.” Five tracks later, though, the prospect of leaving the north has become more appealing. “Cold Weather Blues” is one of the realest songs for anyone who’s ever experienced a Chicago winter, as Waters painfully pines to escape back to the South, “where the weather suits my clothes.” Folk Singer could have been a gimmicky album, considering it’s a complete departure from the kind of music Waters was known for making and a blatant attempt to appeal to the popular sounds of the time. Instead, it’s an incredible hybrid of styles. Waters injects the blues into his acoustic guitar, letting his soul carry the spare 14 tracks of the LP.

Howlin’ Wolf: The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions

Howlin’ Wolf was another Chess Records mainstay, releasing numerous singles and “best of” LPs on the label. This 1971 album consists of recordings Howlin’ Wolf made with the popular British blues musicians of the time, all of whom had been inspired by the early days of Chess Records. Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts all feature prominently on the album, and are credited on the LP’s cover.

The highlight of the LP is the “false start” rehearsal track for “Little Red Rooster,” which is essentially a peek into the artists’ studio session. The song starts, then stops, and then listeners get a peek into the ensuing conversation between Howlin’ Wolf and his British collaborators. It’s not 100 percent intelligible, but it breathes a new sense of life into an already vibrant work.

Etta James: Etta James

Etta James was an outlier on the Chess roster, a powerful singer who, perhaps more so than any of her label mates, blurred the genre lines of rhythm and blues and pushed rock ’n’ roll into new directions. This self-titled album from 1973, not to be confused with her first self-titled from 1962, finds James further experimenting with the concept of genre. It’s basically a funk album, with repetitive grooves and horns forming the foundation above which James flexes her vocals.

The album, released four years after Leonard Chess’ death, found Leonard’s son Marshall playing an increased creative role. Marshall was known around Chess Records for pushing musicians into new artistic territory, most infamously by setting up the psych-rock sessions for Muddy Waters that would become Electric Mud. Although Electric Mud appealed to the rock ’n’ roll style of the time, blues purists reviled it for veering away from Muddy’s signature sound. Muddy, too, claimed to have hated the album.

Under Marshall’s tutelage, James, like Waters, updated her sound in order to fit the popular style of the era. Since James, unlike Waters, was never a genre purist, the experiment paid off. The LP contains only nine tight songs totaling just over 30 minutes, a welcome departure from the more rambling funk songs of the time. And though Randy Newman is hardly known as a funk musician, the album also features three covers of songs taken from his Sail Away album, which was released just a year prior. James’ renditions offer a unique take on the well-known source material, as they tended to do.

Etta James is the strongest LP from James’ later career, which was marred by imprisonment and heroin addiction. James managed to alter her style while still maintaining the essence of what made her captivating in the first place. James was a complicated figure whose albums tended to be hit-or-miss, but this is a fine LP from start to finish.

John Lee Hooker: Plays & Sings The Blues

John Lee Hooker was the rare guitarist whose music was so emotionally communicative it didn’t matter he wasn’t classically trained. Hooker was infamous for not being able to keep a traditional beat, making it almost impossible to set up the kind of studio sessions with other players that formed the basis of the best Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry albums. Hooker obviously had an innate sense of musicality, as his vocals are on-key and his guitar playing is on par with the greats. He simply played what he wanted, as fast or slow as he pleased. This LP’s “Lonely Boy Blues,” for instance, is a staggering work of atypical structure and rhythm that only Hooker could have created.

John Lee Hooker Plays & Sings The Blues is another compilation album put out by Chess as showcase of Hooker’s best songs. The LP has a different vibe than most Chess releases. It’s stripped down like Waters’ Folk Singer, but has a raw blues sound more akin to Fathers & Sons. The recording quality differs from track to track, Hooker’s guitar almost sounds like it’s out of tune, and the lone rhythm section is Hooker stomping on a wooden block. This is as real as the blues gets.

Chuck Berry: The Great Twenty-Eight

The Great Twenty-Eight is nothing more than a greatest hits album, highlighting the best of Chuck Berry’s early career. As the LP’s title suggests, it contains 28 great songs, four sides with seven songs each. The album starts with 1955’s “Maybellene,” and progresses through Berry’s career chronologically, culminating with 1965’s “I Want To Be Your Driver.” There are some repeats from St. Louis To Liverpool on the album, but enough different songs to warrant owning both LPs.

Rock, Rock, Rock

Like Purple Rain or The Harder They Come, the Rock, Rock, Rock LP makes an unsuspecting yet great addition to any vinyl collection because it encapsulates the sound of a specific era and genre in soundtrack form. In this case, the era is the mid-1950s and the genre is rock ’n’ roll.

The soundtrack, Chess’ first ever LP pressing, features songs taken from the 1956 black-and-white film Rock, Rock Rock. The only artists featured on the album are Chuck Berry, The Flamingos and The Moonglows. The latter two groups could be more easily categorized as doo-wop, though, like the other bands of the time, they helped contribute to the new rock ’n’ roll style. The film, which wasn’t necessarily a hit and remains relatively obscure, has a narrative plot but also contains performances from all of the artists featured on the soundtrack.

Jack McDuff: Sophisticated Funk

Jack McDuff is perhaps most well-known to contemporary listeners for making “Oblighetto,” the song sampled by A Tribe Called Quest on “Scenario.” He’s also responsible for many great organ riffs aside from that one, and contributed heavily to the jazz scene of the early 1960s.

McDuff’s lone album on Chess Records is Sophisticated Funk, one of the rare jazz LPs Chess didn’t shift to its subsidiary labels. Despite the album’s title, Sophisticated Funk can be characterized more as soul jazz than funk. The bass and drums lapse into grooves like a funk band might, and vocals weave in and out with touches of Parliament-like flair, but McDuff’s organ playing remains light and restrained.