Breaking Atoms: \"클래식\" 뉴욕 힙합 사운드를 창조한 전설적인 앨범

이번 달의 레코드에 대한 라이너 노트를 읽어보세요

나는 “진정한 힙합”을 믿지 않지만, 바베큐는 믿는다. 어떤 사람들은 힙합의 다섯 번째 요소가 지식이라고 말한다. 다른 사람들은 그것이 불만이라고 주장한다. 개인적으로 나는 바베큐가 힙합 전통의 더 신성한 의식이라고 주장하겠다.

On the West Coast, G-Funk was intrinsically spiced to soundtrack BBQs. Much of the “Nuthin’ But a G Thing” video takes place at a park surrounded by smoked meats, hydraulic cars, and topless volleyball. The Dove Shack’s “Summertime in the LBC” CD should’ve been packaged with a slab of ribs and a pint of macaroni salad. Domino’s “Sweet Potato Pie” skipped the pretense and directly gave you what you wanted.

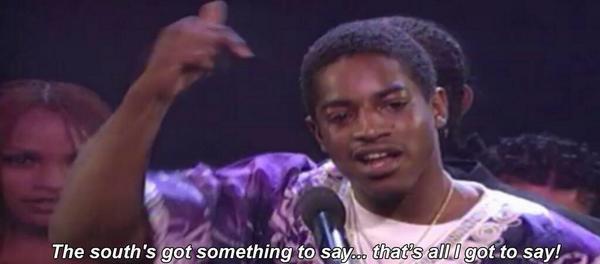

But on the East Coast, for a quarter century running, there’s been only one legitimate frontrunner for the best BBQ song: Main Source’s “Live at the BBQ.” Understandably, you automatically win extra credit with a title like that, especially when you introduce a 16-year old Nas to the world with the greatest debut rap verse in history. But if you really want to understand the indelible quality of “Live at the Barbecue” and Main Source’s Breaking Atoms, I recommend watching this video that aired on the Video Music Box in the summer of 1991.

The bespectacled Large Professor leads the ceremony, backwards cap on, commanding the DJ to stop and re-start the tape. But this time…LOUDER. A dozen on-stage teenagers attempt to mean mug, but they can barely conceal their euphoria. For the first time, they’re about to perform what was immediately hailed as the best posse cut ever (unless you preferred “The Symphony.”)

Large Professor introduces his crew: Joe Fatal, Akinyele, and, of course, Nasty Nas, the Jesus-snuffing prodigy from Queensbridge, already revered as the second coming of Rakim, the God MC. Extra P roars for the DJ to “turn that shit up.” Sleigh bells shake over the boot stomping Bob James drums. Sinuous guitar lines lifted from Vicki Anderson create havoc. The crew simultaneously bang their heads, throw their hands in the air, and then Nas obliterates the binary between heaven and hell. It’s the platonic ideal of what people talk about when they talk about “real hip-hop.”

Of course, “real hip-hop” is usually just a pretentious way to value a certain aesthetic and tool kit. Invariably, this means boom-bap drums with jazz, funk, and soul samples, preferably laced by an SP-1200 machine. There are often lyrics about lyrics, lyrics about the often-arbitrary divisions between real and fake rappers, and virtuosity in technique.

By any metric, Breaking Atoms has everything that defines a traditionally great ‘90s New York rap album. It’s as influential as anything to emerge from the Five Boroughs in 1991 (Gangstarr’s Step In the Arena, A Tribe Called Quest’s Low End Theory)—a sonic bridge between the first Golden Age of Big Daddy Kane and Rakim, and the second one that spawned Wu-Tang, Mobb Deep, Biggie, Jay-Z, and Nas. Yet it reflects something deeper in the psyche and spirit of whatever hip-hop was and whatever rap music became.

At its core, Breaking Atoms is a coming of age record from high school kids being creative and having fun, attempting to figure out interpersonal relationships and adulthood within an environment of oppression and struggle. Something that balanced grimy darkness with the infinite wattage of adolescence—a slow twilight in rap form— an album that grappled with police brutality (“Just a Friendly Game of Baseball”) and the empty hypocrisies of language (“Peace is Not the Word to Play”), but also celebrated the joys of just hanging out (“Just Hanging Out”). BBQ music at its best.

Or better let, let Nas tell it: “Breaking Atoms is timeless,” the rapper told Mass Appeal. “It has more substance than [most albums] today. “Peace is Not The Word to Play” is one of the strongest rap songs ever. Just listen to what he’s saying on that record. And then he gives you a long break and scratches, cuts. It’s hip-hop shit…a real wrecker.”

The group recording Breaking Atoms in studio.

The group recording Breaking Atoms in studio.

The genesis traced back to John Browne high school in Flushing, Queens. A pair of Toronto-born, New York-raised brothers named Sir Scratch (Shawn McKenzie) and K-Cut (Kevin McKenzie) heard about a classmate who called himself Paul Juice, rumored to possess preternatural rap skill and abyssal crates of jazz-funk records.

Tracking him down, K-Cut invited the future Large Professor to their house to audition for their mother. He passed the test, she became the group’s manager, funded their first two independently pressed 12” inch singles, and most crucially helped them track down Ultramagnetic MCs producer, mixer, and engineer, the late Paul C.

Often overlooked in the annals of music history, Paul C helped produce the classic, Critical Breakdown and was one of the first to master the SP-1200—which offered only a few seconds of sample time—but more than enough to revolutionize the sound of hip-hop. Under Paul C’s tutelage, Large Professor quickly developed a reputation as a teen prodigy, one validated by his stellar production work on Kool G Rap’s Wanted: Dead or Alive and Eric B & Rakim’s Let the Rhythm Hit Em. When Eric B skipped some of the studio sessions, the rapper/producer, born William Paul Mitchell even managed to sneak in Nas to record what became his demo.

After the success of their self-pressed single, “Watch Roger Do His Thing,” several labels came calling, but the group ultimately signed with Wild Pitch, the imprint of their close friends Gang Starr. You could argue that during the interregnum between their first single and the eventual release of Breaking Atoms (July 23, 1991), the Large Professor was the most influential man in hip-hop. He taught Q-Tip, Pete Rock, and DJ Premier how to use the SP-1200, even passing on the Tom Scott sample to Rock that eventually became the loop for “T.R.O.Y.” Whether you know it or not, when you think of “classic New York hip-hop,” you’re thinking about the template that Large Pro helped create.

The breakthrough arrived with “Looking at the Front Door,” a slightly melancholic and reflective hit that topped the rap charts, buoyed by a exuberant Donald Byrd riff and weighed down by the failing relationship documented in the Large Professor’s verses.

“As I go on in life, I think more and more about what that song is really about, and it’s really too deep,” Large Professor told Complex. “At that time in life, I was eighteen years old. It was a kid with a pure heart, just writing, and putting his soul out there for the world.”

Released in the fall of 1990, the video is so sincere as to show the couple walking hand and hand on the beach (while Sir Scratch and K-Cut kill time, idling solemnly in lounge chairs). It’s a tale of puppy love lost (“we fight every night and that’s not kosher”) elegiac and simple in its conception and execution—ideal for a playlist alongside the Pharcyde’s “Passing Me By,” Nice and Smooth, “Sometimes I Rhyme Slow,” and Pete Rock & CL Smooth’s “T.R.O.Y.”

By the following spring, Breaking Atoms was the year’s most anticipated debut. In the March/April issue of 1991, The Source devoted a multi-page spread to the 18-year old Large Professor, “the hottest new producer/lyricist in New York.” The article began, “What is a Large Professor? Only the best kept secret in hip-hop.”

Asked to explain his forthcoming full-length, the Large Professor distilled his group’s intent: “What Breaking Atoms is all about is that we consider the rest of the rap industry an atom. And everybody’s tryin’ to follow behind people and sound like Kool G Rap or LL. What we’re trying to do is break up all the atoms and not sound like anyone else.“

If the most artesian version of hip-hop is that wild style—unfiltered originality without regard for arbitrary rules—than Main Source served as its vanguards for that third generation. Of course, immediate predecessors existed. Dre loomed monolithically in the West. In the East stood the Bomb Squad, Marley Marl, Brand Nubian, Boogie Down Productions, EPMD, the Native Tongues, Gang Starr and Pete Rock. But Main Source could pare Kool G Rap rhyme schemes with the sonic ingenuity of Marley Marl, the occasional levity of Tribe and the social consciousness of Chuck D.

When the album finally dropped that July, The Source wrote a rave 4.5 Mic review (later revised to a perfect 5 Mic classic):“Breakin’ Atoms [sic] is New York hip-hop at its best. Its slamming beats and smooth, nod-your-head-to-this grooves thick with jazz-infused samples. It’s clever rhymes that you want to follow word-for-word…a bright beacon of hope that New York artists can continue to advance rap to new heights of musical and lyrical depth.”

If Tribe Called Quest and Gang Starr touted their jazz affiliations so unabashedly as to practically get Charlie Mingus tattoos, Main Source boasted a more implicit connection. There were no songs with “jazz” in the title, just the sort of fluid interplay between voice, beat, and melody, a style rooted in reimagining rare ‘60s and ‘70s grooves that hadn’t yet been excavated by other diggers.

There was also the willingness to experiment. “Snake Eyes” might have been a venomous rant against backstabbers, crooked policeman, and false producers telling lies, but it lay against a beautiful bedrock of Melvin Van Peebles, Ike Turner, and Johnnie Taylor snatches—plus a synclavier, the production tool of choice of Quincy Jones and Frank Zappa. “A Friendly Game of Baseball” feels arguably more resonant today than in the early ‘90s. A lacerating response to police brutality, Large P employs a clever baseball metaphor, calls Babe Ruth a bigot, and expresses his frustration that quick-trigger cops never see proper justice.

If the Large Professor deserves the lion’s share of credit, it’s important to stress the collective efforts of the crew. Pete Rock scored one of his first major production credits with “Vamos a Rapiar.” K-Cut produced “Fakin’ the Funk,” and “Peace is Not the Word to Play.” The sample in “Large Professor” came from an old reggae record plucked from the grandfather of the McKenzie brothers, a soul-disco singer from Guyana.

“Everyone had hands on in terms of like the music. Large Professor would come through and bring samples and bring structured beats and we would all go in the studio and we would all have a hand on it and say let’s add this, let’s add that,” K-Cut recalled several years ago. “We all had something to say about the record. It wasn’t like one person produced it.”

Main Source: Live at the Club.

Main Source: Live at the Club.

This is the strength and weakness of every rap group—the intangible irreplaceable voodoo that exists between collaborators. After all, few things are more invaluable than having trusted friends and talented partners to shoot down your bad ideas and enhance your good ones. In the case of Main Source, financial disputes forced them to part ways shortly after the release of Breaking Atoms.

Extra P went onto help guide Illmatic, as well as producing some of the finest remixes of the remix era. But his own solo career quickly stalled due to label turmoil with Geffen. After Breaking Atoms, it took him another 11 years to get a full-length album in stores. As for the McKenzie brothers, they attempted to find another vocalist, but their efforts soon fell flat. The album was delayed for a half-decade. The moment had passed. What felt magic became mundane.

Maybe that’s partially why Breaking Atoms’ reputation never wavered throughout the last quarter century. There is something pure about it, undiluted by subsequent efforts at commercial compromise or repeating the recipe. A sound can go in and out of style, but there will always be BBQs every summer.

Jeff Weiss is the founder of the last rap blog, POW, and the label POW Recordings. He co-edits theLAnd Magazine, as well as regularly freelancing for The Washington Post, Los Angeles Magazine and The Ringer.