如果您正在阅读这篇文章,您可能已经知道,Vinyl Me, Please 正在重新发行 Townes Van Zandt 的首张专辑,为了歌曲的缘故,作为我们 2018 年 10 月的月度唱片。您可以 在这里注册。但还有其他 Van Zandt 的专辑(以及一部关于他生活的精彩纪录片)值得您的关注。请在下方查看。

I usually bristle when I hear people make absolute statements about art, but it has never bothered me to hear anyone claim that Townes Van Zandt is the greatest songwriter who ever lived. Granted, this is neither provable nor quantifiable (and certainly all the ways Van Zandt lived the textbook Life of A Tortured Genius influence our perceptions of his talent) — but what is true is that when he left the world on New Year’s Day, 1997, he left a stunning body of work: the stories of people living on the margins, dispatches from the places where the sublime meets the shameful, all told with a matter-of-fact drawl and masterful fingerpicking. The songs are so much more than the sum of those parts, though. They draw power from the distinctive way he writes around a feeling without naming it outright, leaving you room to see yourself in the story — and from his ability to empathize and sympathize with the flawed subjects of his songs without whitewashing their cruelty and selfishness.

Van Zandt wrote tragedy like no one else, perhaps because he wrote his own tragedy. Born into a wealthy Fort Worth family, he attended good schools, excelled as an athlete, went to college, made plans to join the Air Force — yet as his sister and his cousin reflect in Margaret Brown’s 2004 documentary Be Here to Love Me, “[Townes] was given lots of opportunities, but I don’t think they made any kind of impression on [him],” and “He didn’t grow up hungry and it bothered him.” Long before his career began and well after it took off, he took terrifying risks, engineered instability and waged a pernicious battle with substance abuse. And even after banking away some money as a musician, he lived in a barely furnished trailer on the edge of nowhere with a bunch of dogs and even more Lone Star.

In his sophomore year at the University of Boulder, Van Zandt lost his long-term memories after receiving insulin shock therapy for manic depression at the behest (and later, profound regret) of his parents. It’s something that never fails to make me queasy every time I re-remember it. Losing your memories is a terrifying prospect for anyone, but takes on a special shade of horror if you write for a living. Writing demands the ability to make elegant connections, to create meaning through context — and both depend on having a good memory. The fascinating side effect of this tragedy is that Van Zandt seemed to compensate by sinking a mile deep into a moment, letting the present create its own context. The downside of this tragedy is that it exacerbated his reckless tendencies and self-destructive behavior. I imagine it’s hard to feel deeply invested in your life if it doesn’t entirely feel like your own.

Living this way damaged or destroyed relationships with wives, children, family and friends — and eventually claimed his own life. By any human measure, it was a sad and selfish way to live; from the perspective of his art, it might have been a selfless act. Was the toll worth it to create the body of work he did? If he hadn’t chosen this life, would he have written with the same insight and intensity? It’s tempting to speculate, if ultimately inconsequential — and, anyway, Van Zandt answered those questions for himself early in his short life. In college, he slowly, elegantly — and on purpose — tipped backward off the fourth story of an apartment building. Recalling the moment, he said, “I decided I was going to lean over and just see what it felt like all the way up to… approaching [the moment] when you lost control and you were falling. I realized that to do it, you know, I would have to fall.”

Townes Van Zandt

Like Keats loping along in a cowboy hat, Townes Van Zandt’s self-titled album finds him writing about love with a balance of remove and passion: charmed by its beauty, awed by its power and deeply aware of all the ways it could go wrong. The music’s simplicity creates a space for his words to shine: just Van Zandt, his guitar and occasionally a harmonica — the way I’ve always liked him best.

Like most profoundly romantic art, Townes Van Zandt is also profoundly sad. Even the songs that describe love in its safest sunbathed moments (“I’ll Be Here in the Morning,” “Colorado Girl,” “(Quicksilver Daydreams of) Maria”) are tinged with wistfulness: a kind of nostalgia for the present moment in the present moment, as though it had already slipped away, creating a distance between the songs’ subjects and their pain or passion. They consider their situations with the clarity of objective outsiders, the dulled vulnerability of a person recalling a tough time 10 years after the fact. “For the Sake of the Song,” “Columbine” and “Fare Thee Well, Miss Carousel” (the best song late-’60s Bob Dylan never wrote) offer shrewd assessments of relationships that have run their course: a poet-lawyer making his case for why it’s time to part ways for good. Even “Lungs” and “Waiting Around to Die,” though they depict life as unrelenting and barely mask fury (Van Zandt himself said “Lungs” should be “screamed — not sung”) are sung with measured resignation. If you weren’t paying close attention, you wouldn’t know how bad things had gotten.

Connection and disconnection loom large in Van Zandt’s body of work, and in his own life. The photograph on the cover of this album depicts the balance perfectly: there he sits, a part of the world around him but apart from it, his gaze trained downward, his eyes closed, a smile on his face nevertheless.

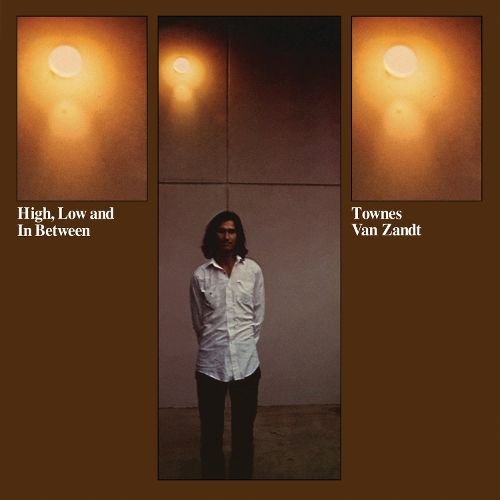

High, Low and In Between

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Van Zandt excels at writing about gambling and religion; neither are for the risk-averse, and both encourage their followers to see and live their lives in imbalance: a do-gooder ever-vigilant against temptation, a loser who never gives up because he just knows he’ll hit the jackpot one day. Gamblers and churchgoers alike live at the mercy of the systems to which they’ve pledged their allegiance — systems that dictate their every move, yet seemingly offer the option to walk away at any moment. You could always just leave the flock or fold your hand, it’s true — but few do. It’s not so easy to leave the thrills of the highs and lows behind.

HLIB leans all the way into that conundrum. There are laments about wasted time and chances (“To Live Is To Fly”), regrets of spitting directly in the eye of goodness when it finally finds you (“Greensboro Woman”) and tales of tables turned (“Mr. Mudd And Mr. Gold”). There are stories about leaving, whether it’s giving the metaphorical finger to a place that’s grown stale (“Blue Ridge Mountains”), answering the call of a higher power (“When He Offers His Hand”) or realizing that when you hop a train for someplace better, your problems hop in right beside you (“You Are Not Needed Now”). Each beautifully arranged song deftly teases apart the inherent contradictions in conviction and faith: whether at the poker table or at the pearly gates, you simultaneously need to be unshakable but also comfortable acknowledging that you cannot completely control your fate. It can be a brave and honest way to live, but also a built-in excuse to never assert agency over your life. At times, both were true of Van Zandt himself.

Religion and gambling both ask you to see yourself through the lens of what you lack, and doom you to a life tethered to trying to compensate for that lack. The last verse of album highlight “To Live is to Fly” — Van Zandt’s favorite song he ever wrote and as close as he ever got to writing his manifesto — captures that sentiment in such a simple, heartbreaking way: “We all got holes to fill / Them holes are all that's real / Some fall on you like a storm / Sometimes you dig your own / The choice is yours to make / Time is yours to take / Some sail upon the sea / Some toil upon the stone.” This is an album about aching for new beginnings but accepting disappointing ends with grace. That’s the chance you take when you risk it all — in matters of faith, gambling, and life.

Delta Momma Blues

Delta Momma Blues is a snapshot of the Van Zandt at the height of his creative powers, flexing his storytelling muscles and looking outward as a means of turning inward (he openly acknowledged that several of these songs — namely, “Tower Song” — were written to himself). The album is cleverly paced: It opens with a languid, bluesy cover of the traditional tune “FFV,” whose protagonist’s fate both summarizes and sets the stage for the rest of the album: a man loses his life because he couldn’t be still. The songs that follow unpack that idea through a variety of perspectives, tracing the ragged edges of a life spent running away, consciously distancing yourself from those you care about and those who care about you.

There’s a current of self-awareness that runs through DMB — even light-hearted tracks like “Delta Momma Blues” and “Brand New Companion” are fraught with “don’t fuck it up like you always do” energy — yet even as the subjects of these songs acknowledge their guilt when it comes to driving others away or driving away from others, their contrition always stops short of atonement. Their subjects downplay pain through context, reminding you that your own struggles matter so little in the grand scheme of things (“You can shout in the wind about how it will be / Or you can clench your fist, shake your head” in “Where I Lead Me”), and encourage you to look forward rather than dwell on the past, even if reflecting on your own actions might prevent more heartbreak down the road (“You’re gonna drown tomorrow / If you cry too many tears for yesterday” in “Only Him or Me”). Once you know anything about Van Zandt’s life, it’s tempting to play armchair psychologist with his lyrics — but it’s especially true of the songs on DMB. Though more likely a consequence of untreated bipolar disorder, this album always makes me think about how Van Zandt’s absence of long-term memories contributed to his yen for instability and unbothered attitude toward loss. Why would you be sentimental about what used to be if you’re completely untethered from your own past? And if everything that was important to you left you, why wouldn’t you always try and leave first?

At the album’s end, Van Zandt grapples with the consequences of those questions through two of his best songs: “Rake” and “Nothin’,” both written after reading The Last Temptation of Christ, Nikos Kazantzakis’ character study of a Jesus struggling to stay on the straight and narrow. The skeletal “Rake” draws on the legend of Don Juan, a reckless libertine who gradually becomes a prisoner of the night he created for himself. The even-leaner “Nothin’” is a bit like a postscript to “Rake”: a dispatch from a hell of your own making, pushing others away, running from your troubles but being unable to deny their existence. Van Zandt liked to say he wrote about how things were, but he seems to also know they didn’t have to be that way.

The Late Great Townes Van Zandt

Occasionally, Van Zandt’s managers and producers got fussy with his songs, hoping that diversifying the arrangements would draw a broader audience. Elaborate production rarely yielded the best results — Van Zandt’s songs shine brightest with fewer elements to distract from his lyrics; one woman’s opinion — so thankfully The Late Great Townes Van Zandt makes a superior choice: introducing variety through stylistic diversity. There’s the fingernail-scrape blues of “German Mustard,” the twangy “No Lonesome Tunes” and the tender “If I Needed You,” which would become one of his most popular songs thanks to a Don Williams/Emmylou Harris cover. There are covers: Lawton Williams’ “Fraulein” and a version of Hank Williams’ “Honky Tonkin’” that sounds as anxious and foreboding as the first minute of a paranoid high. And there’s Van Zandt’s wildest wild card: “Silver Ships of Andilar.” It’s Led Zeppelin by way of Gordon Lightfoot: a fantastical tale of an ill-fated journey to a dark land, a message in a bottle sent in last-ditch desperation. You’ll hear it and either think “What the fuck is this?” or “I wish he’d written 15 more songs like this one.”

Late Great also introduced the world to what would become Van Zandt’s most well-known song, “Pancho and Lefty.” To this day I’d bet money that it’s the only Van Zandt song many people can name, and it’s not just because of that Willie Nelson/Merle Haggard cover: it’s because he takes the most distinctive aspect of his songwriting (the way he explores the consequences of bad decisions without shaming the person who caused his own suffering, because isn’t a hell of your own making punishment enough?) and packages it as a simple, straightforward — by Van Zandt’s standards, anyway — cautionary tale. Two outlaws likely based in some way on Pancho Villa and his friend Lefty, are on the lam: Lefty betrays Pancho’s whereabouts to the police, who find and kill him. In exchange, the police let Lefty go free — on the condition that he leaves town and lies low. Lefty lives in exile, alone in a cheap motel in Cleveland, haunted by the cowardly decision he made and doomed to die unremarkable and unremembered while Pancho’s name lives on in ballads.

“Pancho and Lefty” is both romantic and unsparing: the best example of Van Zandt’s ability to simultaneously toast and roast life’s douchebags, as well as his aptitude for extending empathy toward people who make the weaker choice when tested (that’s all of us, at some point). He was quick to shine a light in a dark corner, but his intent was never to blind whoever hid there — only to show us that whatever we most fear lurks in the shadows will likely look familiar to us.

Honorable Mentions:

Roadsongs, Our Mother the Mountain, The Nashville Sessions — and Margaret Brown’s 2004 documentary Be Here To Love Me

Van Zandt made the most of his creative fallow periods, continuing to perform and frequently performing other artists’ work. Roadsongs, released in 1994, chronicles one of those periods. It sounds great — always a welcome surprise for a live album — features charming stage banter and the covers are well-chosen and personally meaningful: several from Van Zandt’s heroes Lightnin’ Hopkins and Bob Dylan, a truly iconic version of “Dead Flowers” and a pretty-good version of “Racing in the Streets.” There are also a few traditional songs in the mix: if you have toes or fingers, the stunning fingerpicking of “Cocaine Blues” will get them tapping; if you have a heart, his version of “Texas River Song” will make it ache.

Our Mother the Mountain and The Nashville Sessions are also well worth your time. The former was Van Zandt’s second album — the one that perked people’s ears up — and the latter was intended to be his seventh album, Seven Come Eleven: his big breakthrough on the heels of The Late Great Townes Van Zandt. But when his label went bust and his manager Kevin Eggers and producer Cowboy Jack Clement started feuding, the recordings came to a halt and languished in purgatory for 20 years. They were finally released as The Nashville Sessions in 1993. Both albums draw connections between love and the natural world, reminding us that both are unbearably fragile and unbelievably powerful; that they share the ability to make an impact that outlasts the experience. Van Zandt’s entire life revolved around setting fire to whatever was good, and both these albums point out the silver lining to a life committed to speeding up entropy. The whole world works to break you down, and you eventually do break down — but every breakdown is an opportunity to be reborn.

Finally: I strongly recommend Margaret Brown’s excellent documentary about Van Zandt, Be Here to Love Me. It is visually arresting, both tender and unsparing: a nuanced look at how the person Townes Van Zandt was shaped by the art he created, the people around him and the trajectory his career did (and didn’t) take. Brown makes the thematically appropriate choice to tell his story in a way that mimics how a memory might surface in your mind — she brings Van Zandt to life through association: old photos and home videos, interviews with the musicians who knew and loved him best, including Guy and Susanna Clark, Willie Nelson, Steve Earle (who shares a terrifying story of the time Van Zandt played Russian Roulette and cheated death three times in a row — right in front of him) and his family members (his sisters and cousins, his wives and his three children). Van Zandt lived a full and complicated life, and the film portrays it as such without overtly romanticizing him or trying to force his life into a neat and tidy narrative. As if to specifically drive that point home, the film closes with a home video of Van Zandt goofing in front of the camera, trying on a series of hats. “High, Low and In Between” plays over the sequence. Its closing thought: “Answers don’t seem easy / And I wonder if they could be.”

Susannah Young is a self-employed communications strategist, writer and editor living in Chicago. Since 2009, she has also worked as a music critic. Her writing has appeared in the book Vinyl Me, Please: 100 Albums You Need in Your Collection (Abrams Image, 2017) as well as on VMP’s Magazine, Pitchfork and KCRW, among other publications.