10 najlepszych albumów afrobeat, które warto mieć na winylu

Afrobeat — hipnotyczna synteza funku, jazzu i tradycyjnych rytmów zachodnioafrykańskich — rozpoczęła swoje życie w połowie lat 60., będąc odnogi gniaźdzeńskiego highlife i nigerijskiego juju. Stała się regionalną sensacją dzięki wydaniu Super Afro Soul Orlando Juliusa w 1966 roku, ale to Fela Kuti, nigeryjski artysta i aktywista, przyciągnął uwagę całego świata. Kuti był płodny — co roku wydawał kilka albumów przez całe lata 70. — a jego osobowość większa niż życie pomagała zbudować międzynarodową publiczność. Pod koniec dekady wpływowe zespoły zachodnie, takie jak Talking Heads i Brian Eno, zaczęły włączać nieskończone vamps i polirytmiczny smak afrobeatu do swojej muzyki.

Podpisowe brzmienie afrobeatu to organiczny przepływ powtarzających się, splątanych partii gitary; wokale w stylu call and response; polirytmiczne figury bębnów, które zazwyczaj gra się przeciwko sobie na połączeniu zachodnich i afrykańskich instrumentów; duże sekcje dęte, które często zawierają dwa barytonowe saksofony; oraz — przynajmniej w nagraniach Kutiego — wielu solistów.

But Kuti is by no means the only afrobeat artist, other important acts — in addition to Julius, mentioned above — include the Orchestre Poly-Rythmo De Cotonou, the Funkees, MonoMono and many others.

In this roundup, we look at 10 great albums from West African artists. But don’t think that’s all there is. In addition to the extensive catalogs of the artists featured here, there are also myriad others, including Western bands like Daktaris (check out their 1998 release, Soul Explosion), Antibalas, Budos and the Chilean group, Newen Afrobeat. There are also a number of afrobeat hybrids like Zion80, a band that merges the rhythms of Kuti with the liturgical melodies of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, and Here Lies Man, who reimagine afrobeat through the filter of Black Sabbath.

At some point, these 10 albums were available on vinyl — sometimes only in Africa — and they’re listed here, for the most part, in chronological order.

Hugh Masekela: Introducing Hedzoleh Soundz

South African trumpeter/flugelhornist Hugh Masekela left his homeland in 1960 following the Sharpeville Massacre — a watershed moment in the struggle against Apartheid — and eventually settled in New York. He released his debut, Trumpet Africaine, in 1963, and established himself as an African-influenced pop instrumentalist. In 1968, his single, “Grazing in the Grass,” peaked at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

In the 1970s, Masekela played with Fela Kuti and later released his own brand of afrobeat with the Ghanaian group Hedzoleh Soundz. Their 1973 release, Introducing Hedzoleh Soundz, was recorded in Lagos, Nigeria, and features the extended song forms and grooves — although not the large horn section — usually associated with afrobeat. The album is also a showcase for Masekela’s lyrical, understated soloing style.

Masekela was outspoken in his opposition to Apartheid and didn’t return to South Africa until 1990, following the release of Nelson Mandela and the legalization of the African National Congress. He remained in South Africa until his death in early 2018.

MonoMono: Give the Beggar a Chance

MonoMono is an afrobeat band from Nigeria and the brainchild of keyboardist and singer Joni Haastrup. Haastrup was a featured vocalist on Orlando Julius’ seminal 1966 release, Super Afro Soul (Fela Kuti also appears on that album), and toured with Ginger Baker in the early ’70s. He formed MonoMono upon his return to Nigeria and released Give the Beggar a Chance in 1973.

Give the Beggar a Chance is classic afrobeat. It features killer grooves, especially on tracks like “E ja A Mura Sise” and “Kenimania,” but with fuzzed-out guitars and organ instead of a horn section. It also has a subtle psych vibe on songs like the title track and “The World Might Fall Over.”

Orchestre Poly-Rythmo De Cotonou: Echos Hypnotiques - From the Vaults of Albarika Store 1969-1979

Saxophonist Clément Mélomé founded the Benin-based Orchestre Poly-Rythmo De Cotonou in 1968. By 1970, they were a national sensation. Their music is a synthesis of the traditional instruments and rhythms used in Vodun rituals with western instruments like guitar and organ, funk grooves, and other regional feels (Vodun is a West African religion and the antecedent of new world practices like Haitian Voodoo and Cuban Vodú). The band survived political upheaval and Benin’s economy-crushing flirtation with Marxism, and were still performing at the time of Mélomé’s death in 2012.

Echos Hypnotiques - From the Vaults of Albarika Store 1969-1979 is a collection of the recordings the Orchestre Poly-Rythmo De Cotonou did for the Benin label, Albarika Store. The live clip (below), is a great introduction to their polyrhythmic approach to groove (count along to each section’s entrance — if you can!).

Fela Kuti: Expensive Shit

Nigerian multi-instrumentalist and singer, Fela Kuti, is easily afrobeat’s most influential figure — he even coined the term, “afrobeat,” in the late 1960s following a tour of the U.S. — and, along with his longtime drummer and musical director, Tony Allen, established the music’s ethos and sound. Also during that early American tour, Kuti befriended American civil rights activists and embraced the Black Power movement. Radical politics were a major part of his music, message, and — in addition to his popularity as a musician — made him a controversial figure in turbulent, post-colonial Nigeria.

Kuti’s musical output throughout the ’70s was prodigious and consistent, and if you’re looking for an introduction to afrobeat, you can’t go wrong with any of his recordings from this period. Highlights include his 1971 collaboration with Ginger Baker, Live!, Gentleman (1973) and Expensive Shit (1975).

Expensive Shit was named in reference to a government raid on Kuti’s compound, which he called the “Kalakuta Republic,” in 1974. The police tried planting a joint on him as evidence of wrongdoing. He swallowed it instead. He was arrested and kept in police custody until the “evidence” passed through his system. However, his sample — with the assistance of other prisoners — was exchanged for a pot-free sample, and he was eventually released.

Expensive Shit bears all the hallmarks of Kuti’s music: extended song forms, hypnotic and repetitive grooves, a large ensemble including a full horn section and two baritone saxophones, intricate guitar textures, call-and-response vocals and multiple soloists.

Tony Allen: Progress

Tony Allen joined Fela Kuti’s Africa 70 in 1969. He was the band’s drummer and de facto musical director, and he stayed in the band until the end of the ’70s.

Progress is Allen’s first album as a leader. It was released in Nigeria in 1977. The band is Kuti’s Africa 70 — and Kuti makes an appearance as well — but features Allen’s compositions and a number of different vocalists. There are only two songs on the album, both about 10-minutes long, and Allen takes his time developing themes and giving his soloists room to stretch out.

Since leaving Kuti’s band in 1979, Allen has collaborated with British alternative rockers (like Damon Albarn and Paul Simonon), dabbled in hip-hop, recorded numerous solo albums and recently released a tribute to jazz legend, Art Blakey.

The Funkees: Dancing Time: The Best Of Eastern Nigeria's Afro Rock Exponents 1973-77

The Funkees come from eastern Nigeria and had a substantial local following before relocating to London in 1973. They established themselves as a major force on London’s burgeoning West African/Caribbean scene, but disbanded in 1977, although some of their members stayed active playing sessions and touring.

The Funkees’ grooves draw from the same pool of rhythms as many of the artists featured here, although they don’t have a horn section and their sound is more guitar-centric. Dancing Time: The Best Of Eastern Nigeria's Afro Rock Exponents 1973-77 is a compilation of their Nigerian 45s and selected tracks from their U.K. releases.

Orlando Julius and the Heliocentrics: Jaiyede Afro

Nigerian artist Orlando Julius is one of afrobeat’s founding fathers and his 1966 album, Super Afro Soul — which also features Joni Haastrup and Fela Kuti on trumpet — helped define the genre. He worked regularly in Nigeria, but didn’t come to international attention until the reissue of Super Afro Soul in 2000. Since then, he’s been touring and recording. Jaiyede Afro is his 2014 collaboration with the U.K. act the Heliocentrics.

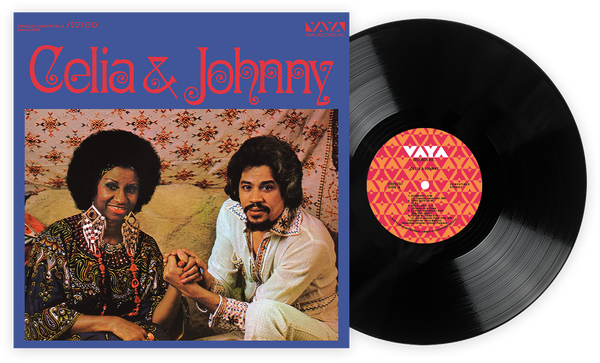

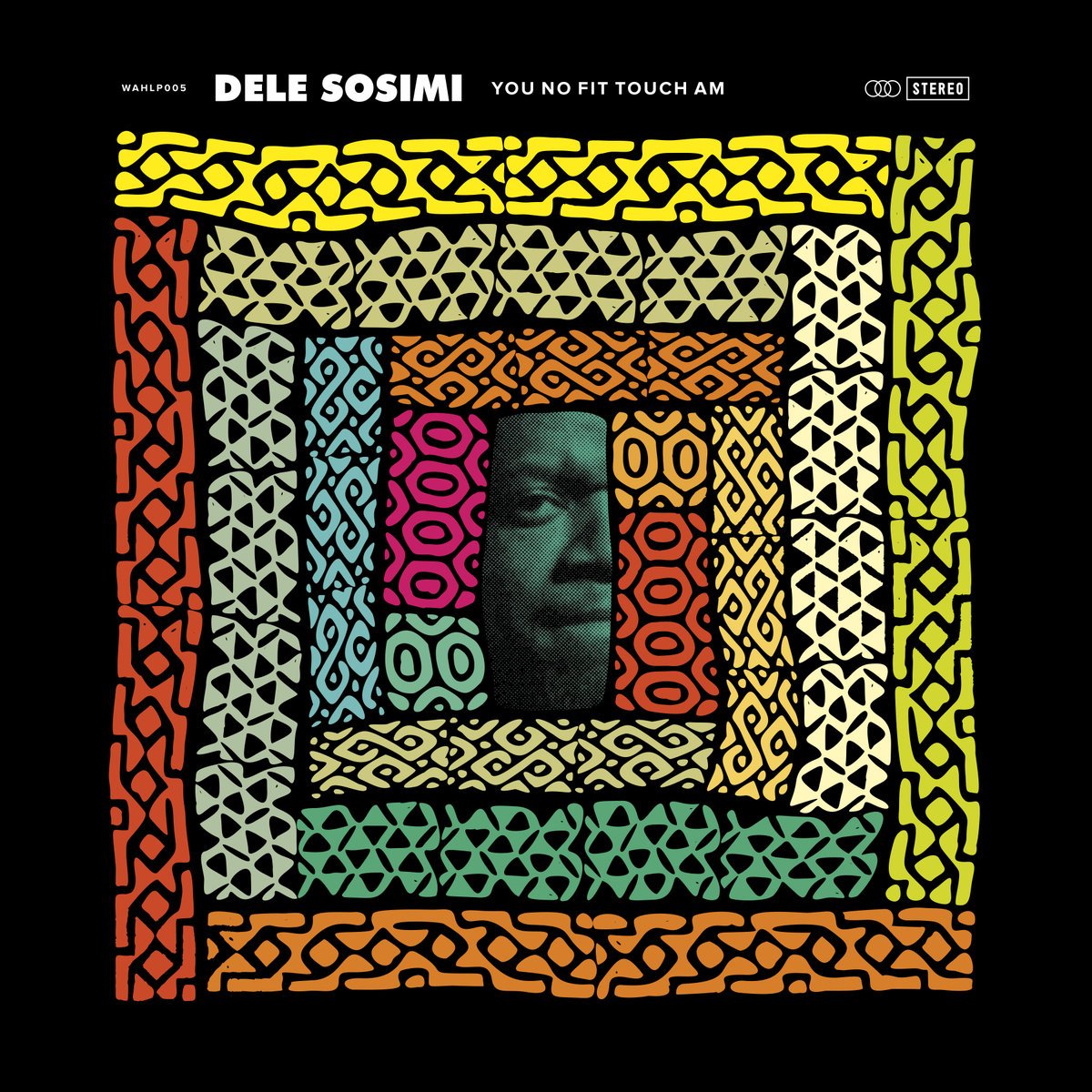

Dele Sosimi: You No Fit Touch Am

Keyboardist Dele Sosimi was born in the U.K., but grew up in Nigeria and joined Fela Kuti’s Egypt 80 in 1979. He was in the band for seven years, including their 1984 performance at Glastonbury. After Kuti was imprisoned in 1984, Sosimi served as the band’s musical director, which was then under the leadership of Kuti’s son, Femi.

Sosimi left Egypt 80 to form Positive Force with Kuti in 1986. In addition to his solo work, he frequently collaborates with Kuti, Tony Allen, and many others. His 2015 release, You No Fit Touch Am, shows off his deep afrobeat roots, arranging chops, and funky keyboard work.

Seun Kuti: Black Times

Seun Kuti, Fela Kuti’s youngest son, took over Egypt 80 after his father’s death in 1997. He was just 14 at the time. The band’s current lineup has some newer faces among the old-timers and their latest release, Black Times, features guest appearances by Carlos Santana and Robert Glasper. Kuti, like his father, wears his politics on his sleeve and the album’s grooves ooze political and social consciousness.

Tzvi Gluckin jest freelancerem i muzykiem. W 1991 roku był w zapleczu Ritz w NYC i stał obok Bootsy'ego Collinsa. Jego życie od tego czasu nigdy już nie było takie samo. Mieszka w Bostonie.

Related Articles

Dołącz do klubu!

Dołącz teraz, począwszy od 44 $Ekskluzywna 15% zniżka dla nauczycieli, uczniów, członków wojska, profesjonalistów w dziedzinie zdrowia & pierwszych ratowników - Zweryfikuj się!