毎月の最初の日は私たちの月間ラップコラムです。これは2017年の15の最高のラップアルバムです。

On 6 Kiss, Lil B wrote about being online as a physical experience: slumped shoulders, creaky neck, eyes glazed over. That record’s long-delayed companion piece, Black Ken, was made by hand. The savant from Berkeley took months off from releasing music to learn how to produce, and the result is something that sounds simultaneously like it’s from 1988 and the next three millennia.

Beautiful Thugger Girls would be the year’s best EP, and it wouldn’t be close. The front half is a revelation: naked, confounding, joyous and, a couple times, lustily, breathily suicidal. “Daddy’s Birthday” is drippingly sentimental, but somehow vital; “Do U Love Me”’s monogamy is rigid as its money is camouflaged. This isn’t the rap-warping post-Cash Money masterpiece Young Thug seems capable of––it’s more like a gin-soaked tropical vacation in the far future. Speaking of Future, the “Relationship” video is a faux mail-order VHS ad, and maybe that’s an apt metaphor: the record’s back half isn’t quite as potent, but if you catch it in the right light, at 3 a.m. via scrambled satellite connection, Beautiful Thugger Girls is the most delirious fun you can have.

Unless you’re DatPiff, it can be very hard to monetize DatPiff. By the end of 2013, the Migos had a major hit under their belt; by the end of 2014, they were being [trotted out] as Exhibit A in Lyor Cohen’s case for Data as the greatest A&R. But the coronation never really happened. There were legal gauntlets and creative ebbs and flows––including a period where the North Atlantans fixated drearily on their status as unappreciated innovators, a tic that cast them as grumpy elders before their debut album hit shelves (which it eventually did, with a creative and commercial thud). Culture is the relaunch. The trio (well,) had stumbled onto a massive single; this was supposed to be the definitive Migos album, their underground appeal formatted to fit your screen. It’s not that. It’s a little weirder, a little gentler––especially on the back half, where there are sneakily emotive electric guitar riffs, somber pianos, trips out of the way––to Mom’s house.

The Mustard Seed reveals itself slowly, a maze of anxieties and double shifts waiting tables at an Olive Garden. Why Khaliq is from St. Paul, Minnesota, and is at his best when transposing the feel of sprawling Southern rap epics to the brutal Midwestern cold. “Anita” is gorgeous and eccentric; “The Mustard Seed That Grew” is the most thoroughly earned exhale I heard all year. Khaliq is a unique talent for his ability to foreground his acrobatic writing and rapping at one moment, then to pivot and let the atmosphere seep through at the next. He grapples with questions of time and capital and family: does he owe it to his newborn daughter to give up on music and find a steadier 9-to-5? Or does he owe it to her to double down and become the person he aspires to be?

Never trust a rap fan who wouldn’t put cash on the table to hear Snoop Dogg rap. Neva Left is an exceptional late-career effort that stakes itself on execution alone, rather than questions of legacy or mythmaking. I mean, it opens with him freestyling for five minutes over the “C.R.E.A.M.” loop, calling himself “the Miles Davis of gangbanging,” which he is. It’s hard to overstate how low-stakes and high-precision all of this is: Snoop ropes in Meth and Red for one song about weed, then Devin the Dude for another; he sort of remakes “The Moment I Feared”; he slinks through extended metaphors about wide receivers and giddily convoluted tales of indiscreet Long Beachers. It’s a joy.

How depressing that when Wins & Losses came out, Meek Mill was presumed to be reeling from [the Drake beef/his tabloid breakup/whatever]. Even before his current legal nightmare, Meek was neck-deep in lawyer fees and searching for answers in his raps, trying to spin motivational fury into something that gave life order and discernible arcs. Wins & Losses has one of the year’s best songs (the Young Thug-assisted elegy “We Ball”) and some bloodlettings, like “Heavy Heart” and “1942 Flows.” A lesser rapper emulating Meek’s style would seem to be stuck in one gear; Meek keeps the intensity high, but leverages his vocals against one another bar by bar to create dynamics and emotional punches. There are a few misadventures in pop that keep the record from truly transcending, but when the blinders are off, Meek is nearly peerless.

Before they became one of the most furious, hilarious, arresting duos in rap, both Don Trip and Starlito kicked around in major label machinery, projects sitting on shelves while they budgeted their advances for groceries and rent. On “The 13th Amendment Song,” they unpack just how black men and women in America are boxed in by banks and officers, judges and gentrifiers.

Who Told You To Think??!!?!?!?! is a record about craftsmanship. The ephemeral is meted out slowly and reshaped by hand. Where Milo once self-deprecated all over his own records, he’s now sunk himself deeply into the finest points of the profession, to the point where the album’s closing song, the Busdriver-assisted “Rapper,” could have been yanked straight from underground compilations during the Freestyle Fellowship boom. Milo pushes in quiet moments––a note to his wife that’s underscored by the danger of being black in America––and hits both singles out of the park. It’s a record composed of heady things that you can still feel viscerally.

03 Greedo’s catalog is intimidating––he puts out an incredible volume of music at a breathless pace. The Watts native has described his work as “emo music for gangbangers,” which is a great hook but doesn’t quite capture how many styles he embodies: he can make neo-T-Pain slow burns laced with dread and contempt, or he can hop, skip, and jump giddily around skull-rattling rap production. “Money on Yo Head,” buried 22 tracks into the excellent Purple Summer 03: Purple Hearted Soldier sounds as if it could come from one of the young Atlantans running rap radio, but two songs later, on “Gudda Shit,” he’s unmistakably Angeleno. Money Changes Everything spends much of its 94-minute run time fretting over those who might abandon him while he’s behind bars. Greedo’s a gripping writer and a slippery stylist, the sort of artist who’s bound to break out soon––but good luck trying to imagine what that first national hit might sound like.

Rosecrans, an expansion of the EP that Problem and the Compton legend DJ Quik released last year, is full of gorgeous suites and long instrumental breaks, the kind of album designed for driving L.A.’s major arteries at 3 a.m., when they’re almost completely deserted.

South Central’s G Perico made two of this year’s best rap albums: All Blue and this month’s 2 Tha Left are both funky, breezy, deeply cinematic spins on pimp rap and G-funk. Perico’s funny, mean, loose, and unpredictable, like Eazy-E if he relaxed a little bit. He’ll let slip a few stray mentions of the bullet wounds in his hip, but seems more concerned with the undercovers lurking at red lights. He’s a solid hook writer, but his work transcends because his verses, delivered in a nasally sneer, are structured musically, and all the manic runs and cackling tangents tie up neatly. He’s one of the most exciting young rappers on either coast.

The climax of DAMN. is “FEAR.,” a slithering, eight-minute song that opens with a Deuteronomy-hawking voicemail and builds to Kendrick Lamar, alone in a hotel room, parasitic accountants siphoning off his wealth, his spiritual impurities keeping him from writing a new song. Back to Section 8, back to the terrestrial. It’s easy to picture this as the very same hotel room from To Pimp a Butterfly, where Kendrick was buckling under the weight of being a black celebrity, and all that entails. DAMN. is about the worry that, unlike race in America, salvation leaves no web of history to unspool, no enlightened thinkers to read for solace, no Justice Department reports to cite. It’s opaque and unknowable. Kendrick headfakes toward the idea of predeterminism––the excellent “DUCKWORTH.”––but allows his writing to sink into the flat chaos of Earth. God comes through in moments like, from “LOVE.,” the eager text message: “I’m like an exit away.”

On HNDRXX, Future is trying to scrape together a quiet life of yachts and islands and women he barely knows. Released just a week after the bludgeoning self-titled album that spawned “Mask Off”––or “Feds Did a Sweep,” depending on your taste––HNDRXX spins Future’s long-dormant pop skills to make one of the year’s sunniest, silkiest, most irresistible records. (That “Fresh Air” didn’t dominate radio through the summer is maybe the greatest injustice of 2017.) The undercurrent is regret: the album ends with “Solo” and “Sorry,” each of which find him hollow and horrified, as if the last 45 minutes of celebration were just a welcome diversion. Overlooked though it was, this is Future’s most dynamic effort since Pluto, and maybe even his best.

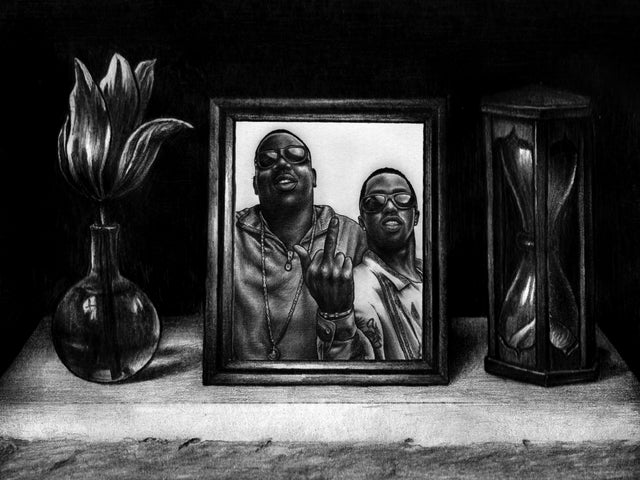

The writing on Rome is rewardingly dense: Elucid and billy woods are two of the genre’s sharpest voices, and their interplay here is tic-laden, novelistic, genuinely stunning. What makes the new Armand Hammer record irresistible is that before you follow it into dreamstates where “the Henny flowed like rivers, and the blunts was like Shaq fingers,” it simply knocks. See the overwhelming villain’s theme on “Shammgod,” the frenetic “Dead Money,” the darkly dissonant “Microdose.” Rome traces New York rap from its formalist center to its most experimental fringes, warping and morphing it in innumerable ways.

Open Mike Eagle’s first solo album since his 2014 masterpiece, Dark Comedy, is a crushed and crushing remembrance of the Robert Taylor Homes, a housing project in Chicago that Eagle spent time in as a child. Since those days, he’s moved across the country to Los Angeles, caught the Project Blowed ghost at the end of its storied hold over L.A.’s underground, and made some of the country’s most gripping rap music. Brick Body Kids Still Daydream is not a life- or even skill set-spanning work; it’s more like a perfect aside, an allegory for matters of race and class and how we relate to the brick and mortar around us.

Paul Thompson is a Canadian writer and critic who lives in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in GQ, Rolling Stone, New York Magazine and Playboy, among other outlets.