Kanye West menyanyikan blues

Trying To Decode The Significance Of Kanye Sampling Nina Simone Over His Career

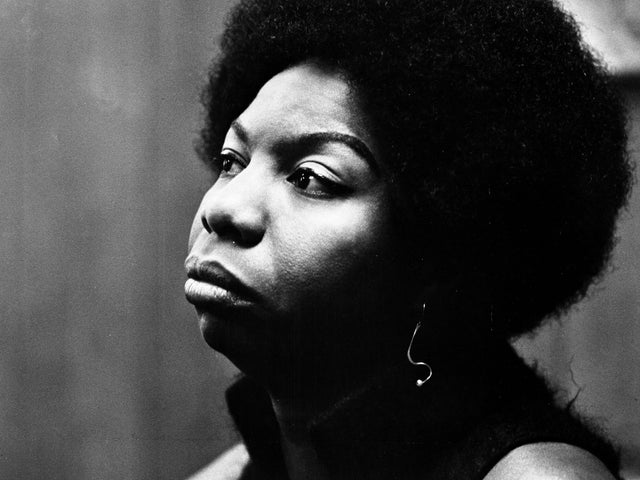

Nina Simone tetap menjadi salah satu artis yang paling dihormati dan dirayakan dalam sejarah Amerika, tetapi dia juga mungkin menjadi salah satu yang paling banyak diambil sampelnya. Renungan tentang kehidupan, cinta, kebebasan, dan tubuh kulit hitam telah digunakan kembali dan ditafsir ulang selama beberapa dekade; sejumlah panjang artis mencoba menjaga warisannya tetap hidup dengan membangun di atas cetak biru musiknya yang dapat mencintai Anda dengan kepalan tangan yang terkatup.

Kanye West adalah perwujudan hidup dari ide ini, membandingkan musiknya sendiri dengan kopi pagi sebagai cara untuk memulai kepercayaan diri seseorang untuk menghadapi keberadaannya. Tetapi implikasi politik selalu ada di sepanjang katalognya juga. Mungkin takdirnya bahwa ia telah mengambil sampel Nina lima kali dalam kariernya, setiap saat lebih disengaja dan berbeda dari yang sebelumnya. Bagaimana dia memanggilnya, dan mengapa? Apakah metodenya berubah? Bagaimana dia berdialog hari ini dengan tahun-tahun lalu dengan cara yang inovatif?

Dalam rangka merayakan rilis VMP bulan ini, saya menyelami lima album Kanye yang memiliki sampel Nina Simone untuk mencari benang kesamaan dalam aktivisme mereka untuk rakyat dan hubungan mereka dengan jiwa. Ada waktu untuk berjuang, untuk mundur, untuk menuntut lebih banyak dari diri sendiri seperti dari dunia. Saya menemukan bahwa semua yang di atas adalah benar, dan banyak lagi ketika merenungkan pertumbuhan karya-karyanya melalui cara Ye memanggil Nina untuk membingkai kekuatan kata-katanya. Anda akan menemukannya dalam keadaan paling marah, putus asa, penuh harapan, dan tak tersentuh dengan Nyonya Simone yang membimbing tangannya.

"Get By" (2003) -> "Sinnerman" (1965)

Kanye’s first documented Nina sample came before his own breakout as an MC, the pre-College Dropout era where a young Ye was in NYC gettin’ beats off to Hov and anyone else he could work with. On Talib Kweli’s “Get By,” a signature single in Talib's catalog, Kanye uses the Nina interpretation of “Sinnerman,” a piece of traditional Black folk music depicting someone calling on the Lord to fight against their demons and ask for forgiveness. The claps found in the middle of Nina’s piece are flipped percussively, backed by their own melody and a drum break with a pitched-up Nina Simone crying out to the Lord at the very beginning.

The claps and melody are later backed by Talib’s voice and subject matter of perseverance through systemic oppression, capitalism, and the prison-industrial complex among many other issues found in the New York, the America he comes from. Talib extends his own hand to the blues and folk tradition by documenting the plight of his people; the framework from the Nina record is met with a live gospel choir for the chorus, giving a warm, updated texture to the religious overtones found in “Sinnerman.” It’s a perfect storm of symbolism: Black artists paying tribute to their ancestry by updating a tradition with a brand new soul.

"Bad News" (2008) -> "See-Line Woman" (1964)

This piece is a more subtle callback to Nina’s work, focusing much more on the thematics of the original while offering a minimalist bridge to the present. “Bad News” is a remorseful ode to a lover scorned, detailing Kanye’s reaction to learning that his lover’s a cheater who ran off with his heart and defaced the love he had for her. In “See-Line Woman,” Nina sings of a heartbreaking woman who can dress and howl, take a man’s money, and leave him in the dust without a second thought about it. Here, the gender roles shift the context: where Nina’s song comes as a forewarning to the world, Kanye’s song is a first-person account of being a victim of the very woman she sang about all those decades ago, though he claims he wrote some of it from a woman’s perspective.

Kanye’s 808s & Heartbreak period incorporated heavy synth-pop and Auto-Tune before the hip-hop of the era had fully caught on to either as a default mode of creation. Upon the release of 808s, many couldn’t bare to call it a rap album because of the heavy, artful pop space he occupied on the heels of bad romance and the loss of his mother, the late Donda West. The subtlety comes in the drum break: he takes the backing of “See-Line Woman” and basses it up, layering the synths, piano, and strings to give him just enough space to croon. Half the record is a ride-out with no vocals, where Nina’s song emphasized the weight of her voice to fill the space between the sporadic percussion and the men backing her.

"New Day" (2011) -> "Feeling Good" (1965)

Kanye and Jay’s Watch the Throne was a hypercapitalist thrill ride with a few tender moments to spare between the classic moments of maximalist flex rap. “New Day” is that tender outlier, peeling itself away from the album’s grander moments of critique - comparing Iraq to “CHIRAQ” and arguing the case for more Black wealth - to host an insular, personal moment of self-reflection between two men on the brink of fatherhood. As Nina sang of a brand new world, turning to symbols of nature and peace to articulate the freedom of a brand new day, The Throne flipped and pitched her samples again, marking the first time he reorganized her phrases to recontextualize the original intent.

With the help of RZA and Mike Dean, Nina’s chops drive the weighty instrumental through its own uncertainty, back to a triumphant refrain of horns and dark piano. The “new life” and “new day” speaks of a redemption through the next generation. For Kanye, who blames himself for moving his mother to L.A. and ponders forcing Republican ideals on his unborn son to ensure he’s liked by White America. Jay is apologetic for the paparazzi invading his unborn son’s life before he can even take his first steps, and envisions their first drink in the lap of luxury since he’ll never have to sell dope to make it out. Through all their mistakes, amplified for the public, the future of their children becomes the “New Day” as Nina’s optimism provides a guiding light in the darkness.

"Blood on the Leaves" (2013) -> "Strange Fruit" (1965)

I remember reading the song title long before I heard it. I anticipated one of the most poignant political statements of Kanye’s career, with Yeezus arriving on the heels of “New Slaves” projections around the world and several interviews detailing Kanye’s gripes with the racism and classism he faces in all facets of his creativity. This time, he recontextualizes Nina’s version of “Strange Fruit” with a rework of a TNGHT beat to speak on the perils of a relationship gone wrong. The reinterpretation of such harrowing imagery for such a subject matter is questionable at best, but Kanye’s much more confident in pitching Nina’s voice and electing to leave her whole phrases intact throughout the beat.

“Blood on the leaves” and “Leaves” are sampled constantly, the “black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze” are juxtaposed with Kanye’s details about being surrounded by women in lust and passion, and later again as a layer with the interpolation of “Down 4 My Niggas,” referencing the magnolias from “Strange Fruit” as well as the Magnolia projects C-Murder comes from. The piano lingers on, disappearing and reappearing while clashing with the snare patterns and riding by itself during Kanye’s solo outro. Hudson Mohawke - one-half of TNGHT - told Pitchfork: “There’s not an overtly political message in the final lyrics, but in some ways that would’ve been too easy.” But still, there’s plenty to say about the decontextualization of a song about lynching into a trap-inspired song about side bitches where Kanye fans of all races can wait for the drop and initiate the moshpit without even knowing the origin of the sample. Three years since Yeezus and I’ve yet to make the connection myself, but the instrumental execution is of an unfamiliar brilliance.

"Famous" (2016) -> "Do What You Gotta Do" (1968)

In the most timely fashion, “Famous” is Kanye’s most multifaceted Nina reinterpretation to date in terms of shifting the sonic context while maintaining some form of thematic dexterity. It succeeds in ways its predecessor doesn’t: by rearranging Nina’s narrative, having a Black woman pop star interpolating it, and juxtaposing it with another classic record to bring a riveting modernity only hip-hop can provide in such a culture clash. Where “Do What You Gotta Do” is about Nina’s struggle to love someone by letting them go, “Famous” is a commentary on itself, complicating the ideas of love and idolisation of celebrity. It’s an attempt at reclamation of one’s freedom from the clutches of fame and an acknowledgement of everyone’s complicit nature in the whole charade, as evidenced by the confusing video piece with wax figures of famous celebrities all in bed together.

The song begins with Rihanna directly singing Nina’s lyrics as a frame - it even had Young Thug doing the same on an earlier draft - then conjures Rihanna’s voice again for the hook, rearranging a bit of the first verse to shift the perspective. Rihanna could represent herself, a close friend, a crazed fan; the tension lies in such an ambiguity. Nina’s original voice doesn’t appear until the tail end of the second verse, layered underneath the popular sample of “Bam Bam” by Sister Nancy with Swizz Beatz assuming the DJ’s role of rocking the crowd from the record itself. For the first time in Ye’s career, he leaves Nina’s voice from the “Do What You Gotta Do” sample alone, with the lyrics still chopped in reverse order.

Michael Penn II (aka CRASHprez) is a rapper and a former VMP staff writer. He's known for his Twitter fingers.

Kulübe Katılın!

Şimdi Katıl, Başlangıç Fiyatı: $44

Diskon eksklusif 15% untuk guru, mahasiswa, anggota militer, profesional kesehatan & petugas tanggap darurat - Dapatkan Verifikasi Sekarang!