“我感覺就像我幾乎是被綁架去的。我沒有選擇。他們把我抓走,說,‘你現在是軍人了。你屬於山姆大叔,’然後我第二天早上醒來在波克堡,心想,‘這是什麼?剛剛發生了什麼?’

— 威廉·貝爾

It’s a late summer day in New York City, in 1962. William Bell is hanging out before the second night of a two-night stand at the legendary Apollo Theater. He’s been to New York—he wrote his debut hit single, “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” in the city while homesick when he was touring with Phineas Newborn Jr.’s orchestra the summer prior—but never like this before. He’s on a bill with Gladys Knight and the Pips, with Jackie Wilson as the headliner, and “You Don’t Miss Your Water” is a hit blaring out of every storefront and club across Memphis, New Orleans, and cities around the southeast. His plan was to ride the single as long as he and Stax could—the nascent label signed him as their first solo male act after he and his doo-wop group sang backup on the first Stax single, Carla Thomas’ “Gee Whiz”—and then go back to studying to be a doctor like his mom wanted him to, since he wasn’t sure his fame was going to last, and his mom was mad he had dropped out to tour. But then he got a call from home.

“My mom had been trying to catch up with me for a week or two, since we were doing one-nighters up the East Coast, and it was hard in those days to get a hold of someone if you didn’t know exactly where they were,” Bell said. “So, we were at the Apollo for a weekend stand, and she finally got me on the phone, and said, ‘There’s a letter here for you, and it’s from the government.’”

Bell had his mom open the letter, and it was as he had feared: He was due to report for selective service, as the U.S. presence in Vietnam was just beginning to escalate at the outset of the Vietnam War. He had a break between his shows at the Apollo and a couple nights in Washington D.C., so he flew home to Memphis, with proof that he was booked to play nine months of shows, thinking that would be enough to earn him a deferment.

“So I drive over to the draft board, in a brand new car that I had bought the last time I was in Memphis in between dates. I wanted to drive it every minute,” Bell said. “I go in and I tell the sergeant at the desk who I am, and he tells me I was two weeks late for reporting. I told him I want to talk to somebody about a deferment, I’m a singer, I got dates. So he has me go back to a different room, and I think, ‘OK cool, this is going to work.’ They have another sergeant, and the first guy says, ‘We got another one!’ and he has me and three or four other guys raise our right hands and say some stuff. I didn’t know what was going on, really. After it was all over, I walk up to the sergeant and say, ‘Sarge, about this deferment,’ and I can’t tell you what he said, but basically it was, ‘You’re in the Army now.’”

From there, Bell was taken to the Memphis Army hospital, and then shipped to Fort Polk in Louisiana. His uncle had to go pick up Bell’s brand new car—which he had to leave at the draft office—and had to call Bell’s booking agent to let them know he’d be missing dates.

“It was devastating. I’m missing all this money. It was like being on a chain gang. We were digging ditches, laying pipe lines. It was like a culture shock; 48 hours earlier I was playing with Jackie Wilson,” Bell said. “But my uncle told me, ‘Whatever you’re told to do, do it, and don’t question it.’ So that’s what I did. I refused to become a squad leader, or anything, and just wanted to keep my head down. They wanted to break me down, so I was on every single dirty detail. Picking up cigarette butts, peeling potatoes.”

Bell would serve two years in the military, eventually being transferred to Hawaii for 18 months. He went in ’62, and didn’t get back to Memphis until early 1965. While he did manage to record and release some singles while on a break between deployments—and some of them even captured the misery of a drafted soldier, like “Marching Off To War”—Bell was out of music during what should have been the years he was finding his way as an artist.

That two year gap reverberated out through his career. Bell never got to be the big star, but instead, had to write his own songs (some of which have become mega hits and standards, others lost classics of soul) and produce his own records—a rarity on the Stax roster in those days. Those two stolen years also mean he didn’t get the same kind of recognition that his Stax contemporaries have gotten in the intervening years; his Stax catalog is unfortunately incomplete on streaming services.

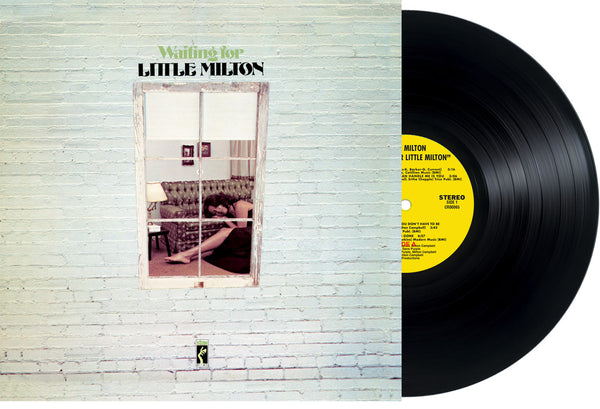

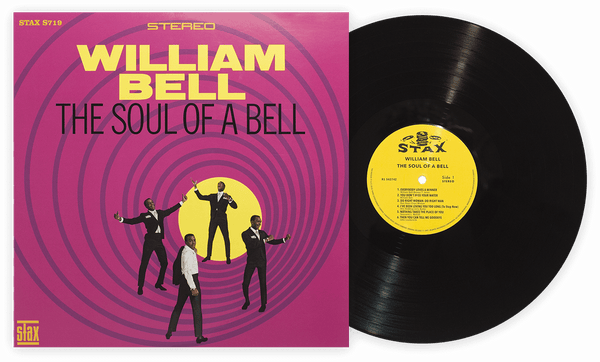

But after a music career spanning more than 60 years, and an undeniable impact on the American songbook, Bell is finally starting to get the mainstream credit he deserves. His Bound to Happen was reissued as part of Stax’s 60th anniversary reissue campaign, and his debut LP, The Soul Of A Bell, is getting an overdue reissue this month via our Vinyl Me, Please Classics subscription. And at 78-years-old, Bell is still an active, touring artist, and arguably made his most well-received album yet in 2016: the Grammy Award-winning This Is Where I Live.

It’s a cold night in November 2017 in Appleton, Wisconsin, and the Take Me To The River tour, a package that is partially in promotion of the film, Take Me To The River—a documentary on the unique musical history of Memphis—has rolled into the Performing Arts Center.

This leg of the tour, in addition to alumni from the Stax Academy—a music charter school next to the Stax Museum complex in Memphis—features raunchy blues octogenarian Bobby Rush, harmonica slinger Charlie Musslewhite, and as the headliner, William Bell.

Bell has been out on the road, with breaks in between, for almost 60 years, first touring as a teenager as part of his doo-wop group, the Del-Rios. He’s done his 10,000 hours, so it’s not surprising that even at 78 years old, you could hear a winter glove drop while Bell was performing. He did power-packed takes of “Easy Comin’ Out, Hard Going In” (from 1977’s It’s Time You Took Another Listen) and “Tryin’ To Love Two” (from 1977’s Coming Back For More), which recombobulated the songs from their disco-fied originals into sprawling, 9- to 10-minute affairs that allowed Bell to work the crowd, slow the songs down to a crawl, and hit notes that you couldn’t imagine anyone being able to hit in a theater in the downtown performing arts center of the sixth biggest city in Wisconsin. But the showstopper and final song of his mini-set is arguably the greatest soul ballad ever recorded, “I Forgot To Be Your Lover.”

“We all had the same problem when we were touring: The road is really hard on our wives, and all of us [at Stax] were on the road so much in those years. You missed your family so much, but you had to do it to keep your name out there and your songs out there,” Bell said. “I wrote that song to try to soothe a lot of entertainers’ families.”

Written by Bell in 1968 after watching Booker T. Jones—of Booker T. and the M.G.’s—try to pry his son off his leg as he was leaving for tour, it’s still Bell’s best calling card, a perfect testament to his vocal talents: It showcases his ability to hit those small, quiet notes, and the way he can sing “sorry” five different ways in 180 seconds. Live, it’s virtually a religious experience. Bell breaks the song down to just his voice at one point; he’s had this song in his arsenal while 10 different men have been U.S. president, so firm is his control of all of its nuances that he could build a house inside of its environs.

Backstage before the show, Bell held court in his dressing room, talking about how fun it was for him to be out on the road, towing the Stax Academy kids along on cross-country tours.

“The response has been incredible. This show bridges the gap between music and generations in a really great way,” Bell said.“It feels like the old days sometimes.”

The old days, of course, are the days in the ’60s and ’70s that Bell spent ensconced in the Stax Records infrastructure. Stax was started as Satellite Records in 1957—the same year Bell cut his first sides as a member of the Del-Rios—but changed its name to Stax, a mashup of the names of brother-sister duo Jim Stewart (who produced) and Estelle Axton (who ran the shop and was basically A&R and promotions in the label’s early days), in 1961. That was the year that the label had its first national hit: “Gee Whiz,” a delicate, sweet ballad of longing written by Carla Thomas, daughter of Memphis MC and singer Rufus Thomas. The song features backing vocals arranged by a local kid whose group was getting some local notoriety at the time: William Bell.

“I had created a doo-wop group to play clubs off Beale Street, and we got this call from Chips Moman to come down and lay backing tracks, because the group they originally booked for the song were singing out of tune and couldn’t get it right,” Bell said, laughing his easy laugh. “They asked me after if I had any songs for us to record as a group, and I sat down and wrote us a couple songs. But then two of the guys in the group got drafted, and I had to go solo.”

Then came “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” the tour with Jackie Wilson, and the military service, and two years shoveling shit for Uncle Sam.

When William Bell rolled back up to Stax in 1965, fresh out of the Army and ready to resume his music career, he came back to an entirely different label. Thanks to Atlantic’s backing, the label was able to sign multiple artists, and turn their homegrown Memphis acts into national stars.

“I got back, and we had superstars!” Bell said. “Rufus [Thomas] had a hit record, Booker had a hit record. Carla was a huge star. And everyone was talking about this group they were going to sign and do something with named Sam & Dave.”

But the biggest emergent star at Stax was, of course, Otis Redding, who by early 1965 had already started to become more myth than man. Though he had taken Bell’s spot as the premiere male solo star on Stax, Bell and Redding got on great; Bell had actually been on leave and recording songs of his own when Redding rolled into Stax studios as Johnny Jenkins’ driver and recorded his debut single, “These Arms of Mine.” Redding and Bell were close—they often toured together—and Redding put Bell back in the game by covering “You Don’t Miss Your Water” on his 1965 album, Otis Blue/Otis Redding Sings Soul.

But still, when Bell came back he was not exactly the top name on the Stax package tour posters anymore.

“When I left I was the first single male artist they signed, and I was on the top of the heap, but then I had to start all over again,” Bell said. “They were giving me songs that were like, secondary. It was the stuff they couldn’t place on the other acts like Sam & Dave and Otis. They were like, ‘Well, William could try to sing this one.’ [Laughs] Some of the songs were good songs, but they just didn’t fit me.”

So Bell resolved to write as many of his own songs as possible, and to write singles for other artists. This was arguably the turning point in his musical career. When the path to superstardom was blocked, Bell did what he did in the military: He put his head down, and got to work. He began working very tightly with Booker T., an old family friend, who lead the Stax house band and wrote and produced on too many hits to possibly list. Stax was busy putting out records by their new superstars, so Bell also taught himself how to produce, and focused on his songwriting. It had always been a facet of his career, but in some ways it became an equal focus for him to performing and recording his own material.

It was during these years that Bell had the most fruitful writing periods of his life. From 1965 to 1969, he wrote massive smashes for other artists, and some for himself as well. He made Ollie & The Nightingales into soul stars thanks to writing “I Got A Sure Thing,” the group’s lone hit, and a top 20 single. He wrote “Any Other Way,” a hit for Chuck Jackson, and he wrote a duet with Judy Clay, called “Private Number” that made her into a star, and got sampled in hip-hop songs. Despite crafting dozens of soul classics in that period, Bell’s biggest selling, most classic song is a blues standard that every bluesman worth his salt has covered, even Homer Simpson. You’ve definitely heard it:

“I was having a day of just hanging out around the studio, learning everything I could. Albert had come in for a session to cut some songs and an album, and Jim [Stewart] came in and asked me, ‘William, you’re always writing songs. You got anything that would work for Albert to record?’ I had the song I was writing for myself, and it was during the time when zodiac signs and that stuff was really hot, and I told Jim all I had was a bassline and a verse and a chorus. I sang him what I had, and he sent me home with Booker T. that night to finish writing it for Albert,” Bell said. “I wrote that line, ‘I can’t read, I didn’t learn how to write’ for Albert, because that was true about him; he couldn’t read or write. I came back the next day, and the M.G.’s laid down the track, and I had to stand behind him in the vocal booth, and whisper the lines to him, because he usually worked by listening to the song a bunch and memorizing it, and he couldn’t do that with that song. I think we did it in just a couple takes, and then he sat down with his guitar and did his thing, and it came to life. And it became his signature song, and then every blues guitarist’s signature song.”

When it came time to focus solely on his own career, Bell’s first solo comeback hit tackled the way he felt when returning to Stax: how he used to be a winner, but felt like the lowliest cog in the machine.

“Nothing was really clicking for me [when he first got back], and being overseas for a year and a half, the music had changed so much. So I asked Jim [Stewart] if I could glue my ears to the radio, and find out what was happening musically in America,” Bell said. “And they let me take some time to catch up. Based on the reaction of everyone in the studio when I came back, I wrote ‘Everybody Loves A Winner,’ and that was my first hit song I had coming back.”

Released in early 1967, “Everybody Loves A Winner” was the comeback single Bell needed. Its opening salvo, “Once I had fame, I was full of pride / there were a lot of friends / always by my side / but my fame, oh it died / and now my friends began to hide” makes it one of the first self-aware comeback singles; it’s a song that eventually brought back the very fame missing in the song’s lyrics, as the song made a dent in R&B charts and is still one of Bell’s most-covered songs.

The song eventually became the centerpiece for his overdue solo LP, The Soul Of A Bell, a record that came out a full six years after his debut solo single. From there Bell had a sensational run of LPs. His sophomore album, Bound to Happen, featured the aforementioned “I Forgot To Be Your Lover,” and Bell’s takes on “I Got A Sure Thing” and “Born Under A Bad Sign.” 1971’s Wow… and 1974’s Relating are perfect slabs of soul perfection, while 1972’s Phases Of Reality is a rarity for the day: a concept album about Vietnam and drug addiction. Relating would be Bell’s last album for the OG Stax though; the label folded up shop in 1975 under a mountain of bad debt. Bell resolved to quit music, again.

“I was still doing some writing and producing, but I didn’t want to be an artist. As kids, when we went to Stax, we never thought it would end,” Bell said. “We got to make the music we wanted to make for so long, and then when it ended the way it did, we were all kind of disillusioned. I needed a change of scenery, and for three years I was basically out of music.”

Bell had planned on becoming an actor, and started taking classes to learn that craft as well as he’d learned music writing. He envisioned becoming a leading man; producers saw him only as a bit player in Blaxploitation movies that Bell didn’t much care for. He was content just being a man-about-town in Atlanta, hanging out in jazz clubs, and occasionally producing other artists. Like Chips Moman had done 16 years earlier, the head of Mercury Records took it upon himself to pester Bell into the studio.

“Charles Fach kept telling me he had wanted to do a project with me going back to my Stax days, and I kept telling him no. And he persisted, until I agreed to cut four sides for them, and they basically gave me carte blanche to do whatever I wanted,” Bell said. “But I had literally no songs; I had used anything I had written since Stax on artists for my own label. So I came up with the idea for “Trying to Love Two,” and ended up linking with the Paul Mitchell Trio, a jazz group that was playing at the jazz club I used to go to.”

Bell signed a two-year deal with Mercury after he recorded his four songs, and then something unbelievable happened: nearly 20 years into Bell’s career, he had a hit single. “Trying To Love Two” hit No. 1 on the R&B charts, and went to No. 10 on the pop charts. It sold a million copies, Bell’s best selling record by a wide margin.

“I was on a flight to L.A. around that time, and the stewardess called over the loudspeaker for me to ring my call bell. So I thought, I wonder what this is about,” Bell said. “She made me stand up, and the captain came on the loudspeaker and said, ‘We have a young man on the airplane who’s sold a million records,’ and I’m in the plane aisle, being like ‘What is happening?’ [laughs]. Turns out my label had called the airline and asked them to do that, and that’s how I found out it was a million seller [laughs].”

The record went gold, and Mercury had him record two full-lengths, but eventually, he rode off into the sunset to do his own thing again, making self-financed albums, and running his new Wilbe Records, which is still in operation close to the airport in Atlanta today. Bell was content to tour intermittently, record albums for his own label, and do his own thing. He did that for almost 40 years, before Stax—relaunched under Craft Recordings in the mid-2000s—came calling.

In 2016, Bell released a comeback album with Stax, titled This Is Where I Live. Recorded with producer John Leventhal, the album features multiple autobiographical songs and a revamped version of “Born Under A Bad Sign.” The album thrust Bell back into the spotlight, sending him out on national tours, and setting him with the Take Me To The River documentary folks. He did a Tiny Desk concert, the modern mark of musical celebrity. But in 2017, he accomplished another unlikely feat: the album won the Grammy for Best Americana Album.

“It was a validation of the years of the hard work and all those years I spent on the road, man,” Bell said. “You read about all the iconic artists who never won a Grammy ever, and I’m saying, ‘In my lifetime, I got a Grammy.’ I’m not a hip-hopper, I’m 77-years-old! [laughs] When they called my name, I couldn’t believe it. My manager had to push me out of my chair, like, ‘That’s you!’ [laughs]. 2017 was a magical year.”

It’s hard to fathom doing something for more than 60 years, and not getting the recognition from your industry that you deserve. But 50 years after his debut LP, and more than 55 from his debut single, Bell is looking at a 2018 filled with tour dates, recording sessions, and yet another round with his music career.

“I feel like I’ve had four separate music careers. I was making music, and then I got drafted. Then I came back, and Stax folded. Then I went to Mercury, had the big success, and then did stuff on my own. And then to come back in 2016, with the new Stax, and get this kind of acceptance has been incredible,” Bell said. “To be 78 now, and to have this kind of pivotal moment in my career, it’s been nothing short of magical.”

Andrew Winistorfer is Senior Director of Music and Editorial at Vinyl Me, Please, and a writer and editor of their books, 100 Albums You Need in Your Collection and The Best Record Stores in the United States. He’s written Listening Notes for more than 30 VMP releases, co-produced multiple VMP Anthologies, and executive produced the VMP Anthologies The Story of Vanguard, The Story of Willie Nelson, Miles Davis: The Electric Years and The Story of Waylon Jennings. He lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota.