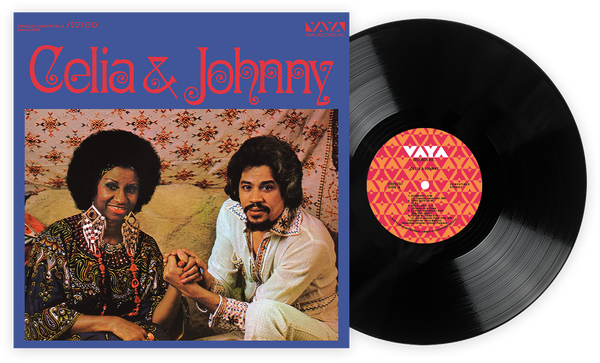

CeliaとJohnnyは文化を融合させ、サルサのクラシックを創り出しました

今月のクラシックアルバムのライナーノーツからの抜粋を読んでください

“ルンバが私を呼んでいる:ボンゴ、彼女にもうすぐ行くと言って…”(“The rumba is calling me: Bongó, tell her I’m on my way…”)

“Rogelio did the paperwork so that Sonora could leave Cuba. Everything was ready except the exit permits that the government had imposed, and because so many artists and important people were leaving, that process was becoming increasingly complicated. I never knew exactly how Rogelio did it to get us all the exit permits, but at that moment he was the only one who knew that after that trip we would never go back to Cuba.”

Those are the words written in Mi Vida (My Life), the autobiography of Cuban singer Celia Cruz (Havana, Cuba, 1925 - Fort Lee, New Jersey, 2003). Rogelio is, of course, Rogelio Martínez, Cuban tres player and director of the most important and successful orchestra the island has seen: Sonora Matancera. Celia was the most acclaimed female member of a large group of unforgettable singers, which included Bienvenido Granda, Celio González, Alberto Beltrán, Nelson Pinedo, and Daniel Santos. With this orchestra, originally from the Cuban city of Matanzas, the singer planted songs that today continue to be universal hits: “Burundanga,” “El Yerbero Moderno,” “Dile Que por Mí No Tema,” “La Sopa en Botella,” “Melao de Caña,” and “Juancito Trucupey,” among others.

A perfect mix of sweetness and character, unbeatable in the art of montuno (the improvisation between chorus and chorus, characteristic of salsa) and owner of a unique and inimitable technique that made her singing a tool, both temperamental and volatile, the voice of Celia Cruz is still impossible to classify. Perhaps there is no better description for her art than that offered in one of the greatest hits of her repertoire with the Sonora Matancera, Ramón Cabrera’s bolero “Tu Voz”:

“Tu voz, que es susurro de palmas, ternura de brisa, / tu voz, que es trinar de sinsontes en la enramada…” (“Your voice, a whisper of palms, tenderness of a breeze, / your voice, the trill of mockingbirds in the bower …”)

After her departure from Cuba to Mexico in July of 1960, Úrsula Hilaria Celia de la Caridad de la Santísima Trinidad Cruz Alfonso was already the “Guarachera of Cuba,” a title given to her for her appropriation of the festive and sweeping “guaracha” style, not only in her singing, but also in her dress, dance and attitude. It would not be long before she also became the undeposable monarch of the musical genre. “As I was the only woman in the Fania group, I was crowned Queen of Salsa,” she recalled in her autobiography, written in collaboration with Ana Cristina Reymundo.

That same year, a young Dominican percussionist and flautist based in New York named Juan Zacarías Pacheco Knipping (Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, 1935), launched his first solo production in the orchestral charanga format (violins, flute, conga, piano, and double bass), with the voice of another former member of the Sonora Matancera, Elliot Romero, for the Alegre record label. He had already made a name for himself throughout the 1950s before making his first solo production, in the Big Apple’s Latin music scene under the name of Johnny Pacheco, alongside pianist Charlie Palmieri, with whom he played in the band Charanga Duboney. The success of “Charanga!” that first solo recording by Pacheco, with 100,000 units sold a few weeks after its release, also led him to become the first Latin musician to play at Harlem’s famed Apollo Theater in 1962. Celia Cruz would arrive at that same stage, two years later. The musician and the singer were chasing each other, without knowing it.

Celia continued working on recordings with the Sonora Matancera until 1965, and began a fruitful working relationship with the orchestra of the King of Timbal, Tito Puente, as a star of the Tico Records label. Meanwhile, in 1963, Pacheco joined the American businessman Jerry Masucci in partnership to create a new label called Fania Records.

Celia remembered having seen Pacheco for the first time in 1969, after a concert by Sonora Matancera at the Apollo. From that moment on, she called him “my dear brother.” Before the recordings, the first thing that united the singer and flautist were the conversations about music, and the reflection of what the word “salsa” meant in the Latin imagination. In her autobiography, she remembered Pacheco telling her: “Whites have their labels, blacks have Motown, and with Fania, we Latinos will have ours too, with our salsa label.”

Like them, a large group of Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Dominican musicians living in New York’s Spanish Harlem and the Bronx, together with their children, first-generation nuyoricans, began to lay the foundation of a music based on danceable sounds of their own countries. This new music had the traits that the format of the big band and the sound of jazz had been contributing to Latin music in New York since the 1940s, thanks to figures like Frank Grillo “Machito,” Tito Rodríguez, Mario Bauzá, and Tito Puente himself; and on the jazz side, Dizzy Gillespie and his lead percussionist, the Cuban Luciano “Chano” Pozo.

That music that was to be born — and that carried all the possible influence of “son,” mambo, cha-cha-chá and Cuban bolero; of “bomba,” “plena,” the Puerto Rican jíbaro sound, and Dominican merengue; plus the styles that preceded it in North America, such as the rhumba, Cubop, pachanga, and boogaloo — would become one of the most original musical phenomena created by the mix of demographics and sound in the United States: salsa. César Miguel Rondón, from Venezuela, author of El Libro de la Salsa (The Book of Salsa), called the genre “the totalizing manifestation of the Caribbean of our time.” Renowned Cuban writer Leonardo Padura Fuentes, one of its most enthusiastic researchers, called it “supreme expression of a new and powerful cultural miscegenation.”

Fania Records became synonymous with salsa for the world, thanks to Pacheco's keen eye for talent and Masucci’s unmatched savvy as a businessman. Eleven years after its creation, it had the deepest roster in salsa, with Willie Colón, Héctor Lavoe, Larry Harlow, Ray Barretto, Pete “El Conde” Rodríguez, Rubén Blades, Cheo Feliciano, Roberto Roena, Bobby Valentín, and, of course, Celia Cruz, all recording for the label. Other famous artists of the salsa movement who recorded with independent labels like Richie Ray and Bobby Cruz, Ismael Rivera, and La Sonora Ponceña, ended up becoming Fania artists when the conglomerate absorbed label subsidiaries such as Alegre, Vaya, Incca, Tico, Cotique, and others.

Probably the highest point in the conquest of the public by Fania was Pacheco's undertaking to create a “Dream Team” with the most famous singers, soloists and orchestra directors who were part of the label. Thus was born in 1968, the so-called Fania All-Stars, a huge big band musically directed by Pacheco, better remembered for its live recordings than for those recorded in the studio — in venues such as the Red Garter and the Cheetah in New York; the Roberto Clemente Coliseum in San Juan, Puerto Rico; the Carlos Marx theater in Havana; the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, Japan; and the Tata Raphaël stadium in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The ill-fated Fania All Stars concert at New York’s Yankee Stadium, suspended after spectators invaded the grass, was well remembered. This situation was fully recorded in the film Salsa, from 1973, produced by Jerry Masucci and director Leon Gast, who had already collaborated on the film Our Latin Thing, in 1971, and which shows the success of the All Stars of the Fania label in the Cheetah.

Celia Cruz’s first participation in a Fania album was in 1973, summoned by pianist Larry Harlow to participate in his salsa-opera Hommy, a clear reference to Tommy, The Who’s rock-opera. It was understood: if The Who had featured Tina Turner in their opera, how could Celia Cruz not be in Hommy? The Guarachera debuted singing the song “Gracia Divina.” Meanwhile, Johnny Pacheco continued inviting talents to his label, acting as the producer of these new albums, without neglecting his own output on records such as Viva Africa (1966), By Popular Demand (1966), La Perfecta Combinación (1970), and Los Compadres (1971). In those recordings he was accompanied by singers such as Justo Betancourt, Rafael “Chivirico” Dávila, Ramón “Monguito” Quián and his great friend Pete “El Conde” Rodríguez, with whom he used to work on his recordings with the Alegre label.

A year later, it was time for Celia and Johnny to meet in the recording studio. The historic moment was fulfilled in the song “La Dicha Mía,” composed by Pacheco, narrating Celia’s artistic life:

“Después conocí a Johnny Pacheco, / ese gran dominicano. / Y con Pacheco / me fue mejor. / La verdad es que con Pacheco / causamos gran sensación…” (“Later, I met Johnny Pacheco, / that great Dominican. / And with Pacheco / I did better. / The truth is that with Pacheco / we caused a great sensation …”)

After Hommy, Jerry Masucci invited Celia to officially join his label under a contract with the subsidiary Vaya, with the condition that if nothing significant happened in sales on a first album, she could return to work with Tico Records. Masucci also gave her the freedom to choose which orchestra of his conglomerate she wanted to record with. She did not think much about it. “I told him: ‘with Pacheco,’ since at that time Pacheco sounded like the Sonora Matancera. He was always a great admirer of the Sonora, so much so that he sang in their ‘coros’ and was the same voice of Carlos ‘Caíto’ Díaz, eternal ‘corista’ of the group.” All that was left was for the duo to make it official on an LP.

For Will Hermes, author of Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever, Celia & Johnny was “Cruz’s formal declaration of allegiance to the new school in her adopted homeland,” in the same way that the role of Pacheco as a partner in the recording is to be considered. “In addition to being Fania's co-owner, able to marshall all its resources, the bandleader and flautist was also, at heart, a traditionalist weaned on Cruz’s early Cuban recordings with Sonora Matancera. Cruz was open to experimentation, but fiercely proud of her tradition. Mainly a set of straightforward Cuban ‘sones,’ Celia & Johnny was played with a killing New York swagger.”

In fact, the Pacheco orchestra had for this recording a “Cuban-like” formation of two trumpets, performed by Héctor “Bomberito” Zarzuela and Luis Ortiz, the piano of Papo Lucca (director of Sonora Ponceña), the double bass of Víctor Venegas, the congas of Johnny Rodríguez, the bongo of Ralph Marzan, the Cuban tres of Charlie Rodríguez, and the coros of Ismael Quintana, Justo Betancourt, and Johnny Pacheco himself, who was also handling flute, güiro, and minor percussion. His love for Cuban music, which he had already channeled through his charanga recordings, now called for the influence of Arsenio Rodríguez, Félix Chappotín, and, of course, Sonora Matancera. The arrangements were made by Pacheco, Papo Lucca, and Felipe Yanes.

Asked at some point which of her own recordings made her feel most proud, Celia Cruz, quoted by Eduardo Márceles in the biography ¡Azúcar!, said she chose Celia & Johnny. The reason, in her brief remark: “Because it was a record with five or six hits.” Fair enough, but there are many great reasons that this album is a total masterpiece of salsa: The Cuban and traditional spirit distilled in each track. The diaphanous voice of the “Guarachera de Cuba.” Pacheco’s adventurous spirit, free from self-importance and, above all, remarkable communication between singer and musician, which resulted in five other Fania productions through 1985. It all started with the classic Celia & Johnny.

Translation by Betto Arcos

Jaime Andrés Monsalve B. has been Musical Director of Radio Nacional de Colombia, Colombia’s public radio network, since 2010. He’s also an Editorial board member of Arcadia and El Malpensante, two of Colombia's major cultural magazines. He's been a cultural journalist and editor of a few Colombian magazines and newspapers. As an author and co-author, he's written books about Tango, Jazz, Salsa, Colombian classical music and Cumbia. In 2011 and 2018, he won the Simón Bolivar National Journalism Award, the most important journalism award in Colombia.