New Albums From Gucci Mane, Brother Ali, DJ Quik, And More Reviewed In 1st Of The Month

1st of the Month is a monthly column that rounds up the best releases in rap music, from major label albums to Datpiff classics. This month's edition covers T-Pain & Lil Wayne, Brother Ali, Gucci Mane, and more.

RJ: Mr. LA

Los Angeles is in the thick of a renaissance so rich and so far-reaching that to properly document it would eat up all the space in this column several times over. Earlier this year, Kendrick Lamar dropped yet another world-beating, critically adored LP which, despite enlisting Kid Capri for a series of drops, is a deeply L.A. record, sunbaked and smog-choked. Last month, G Perico’s All Blue stood out as a neo-Quik instant-classic, music to get perms to, to dodge undercovers to. RJ occupies a different space. Where his friend and collaborator (and now label boss) YG, is unique for emerging from the city’s jerkin’ scene as something new and mutated, RJ popped up fully formed, the product of a South Central upbringing and a brief spell in Georgia. Mr. LA captures all his gifts: a bright, sneering delivery, sneakily motivational writing, and an indelible sense for rhythm. Lead single “Brackin” is already making the strip club rounds, but it’s album opener “Blammer” that should hammer out of speakers through the dog days.

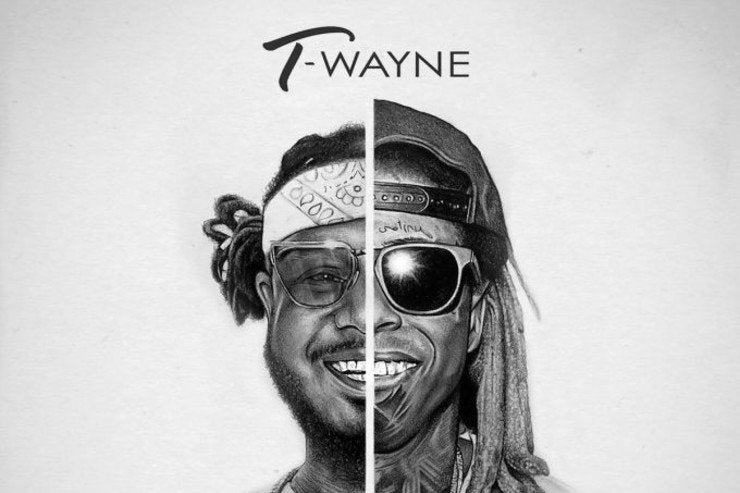

T-Pain & Lil Wayne: T-Wayne

Neither Lil Wayne nor T-Pain needs their long-awaited joint record to cement his legacy, but He Rap, He Sang still stands as one of hip-hop’s great what-ifs. T-Wayne, a hard drive dump courtesy of Mr. Pain (with an assist from Noisey’s Kyle Kramer), is not a fully-realized LP; completists likely have six of these songs sitting in iTunes libraries in various half-finished stages. But it’s still clarifying to hear them arranged like this: T-Pain is the star, a versatile talent who croons the way he did on his biggest hits or raps in a delightfully rough-edged voice that underscores how wide his talents range. “Heavy Chevy,” slotted into the closing spot, is Wayne’s best turn here, a verse where the native Louisianian, displaced to Miami after Hurricane Katrina, rattles off all the things he’s learned from South Florida’s car culture. This is Wayne in his post-Carter 3, pre-No Ceilings phase, when he was drowning in Autotune and probably creatively fatigued. Even playing hurt, he’s one of his generation’s most magnetic figures.

Brother Ali: All the Beauty in this Whole LIfe

Brother Ali has been a sage, wizened presence in Minneapolis for most of my memory. Of course, there was a time when he was the young upstart, rebelling against the structures that preceded him; there was his minor debut Rites of Passage, and the masterful Shadows on the Sun, where the barrel-chested rapper with the booming voice wrestled with his weight, his neighborhood, and the mean-tempered dude across the hall. But in the past decade, as Ali became a true north figure in the city’s political struggles, his work has often read as a journey to the center of his psyche, the sound of a man who was keeping the lights on but wrestling with big questions. All the Beauty in this Whole Life reunites Ali with Atmosphere’s Ant; while Ali’s last album, 2012’s Mourning in America and Dreaming in Color, was crafted by Jake One, Ant has helmed most of Ali’s work in its entirety. Here, he rehashes the suicides of his father and grandfather, and even digs up some of that early-century anger when he sees fit.

Gucci Mane & Metro Boomin: DropTopWop

I don’t care if Gucci Mane ever makes another song in his life. His freedom, health, and happiness is so affirming that any creative work is a footnote. And yet the title of last year’s comeback album, Everybody Looking, couldn’t be more appropriate; during his incarceration, at a federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, Gucci’s influence over the latest generations of rappers has become unavoidably clear. Droptopwop, his full-length collaboration with Metro Boomin, a sort industry grandchild, is his strongest work since the homecoming by a comfortable margin. While Metro continues to bolster his reputation as not only a hitmaker, but a full-bore creative partner, Gucci’s flow has finally been knocked loose, back in the direction of his prime-period careening. Songs like “Met Gala” and “Finesse the Plug Interlude” show Gucci’s vocal range in a way that Everybody Looking failed to. Droptopwop is likely too weird to spawn any hits, but it’s the sound of an artist plodding back to his wheelhouse.

J Hus: Common Sense

J Hus is a remarkably talented young rapper from East London who is banned from playing shows in his hometown because racist policing recognizes no international borders. Common Sense is a master class in synthesis, folding in elements of a half-dozen distinct genres, yet never straying too far from Hus’s emotional center. Along with producer Jae5, Hus (a childhood nickname that’s short for “hustle”) populates his neighborhood with jealous assailants who want him in a casket and preppy university girls who want him in their WhatsApp inboxes. The stateside analogues would be early 50 Cent, when the villainy and the unfiltered joy swirled together and gave us shit like “Heat” and “How to Rob.”

DJ Quik & Problem: Rosecrans

I hid this record at the end of this column so I could sneak this into your brain: DJ Quik is the greatest rap artist in Compton’s history. This is the expanded version of the Rosecrans EP, which he and Problem issued last year and which is a wonderfully locked-in groove long enough for a late-night drive anywhere in L.A. County (everything takes thirty minutes or less). The LP version is everything you could hope for in a late-career turn from Quik, whose production is as sharp and voice as inimitable as ever. Problem acquits himself nicely, and the revolving door of stars (Wiz Khalifa, Game) and newcomers (the impressive Compton-bred Buddy).

Paul Thompson is a Canadian writer and critic who lives in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in GQ, Rolling Stone, New York Magazine and Playboy, among other outlets.

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!