The New Orleans Jazz Genius Who Could Never Be Contained In An Album

The Story Of James Booker’s Lost Paramount Tapes

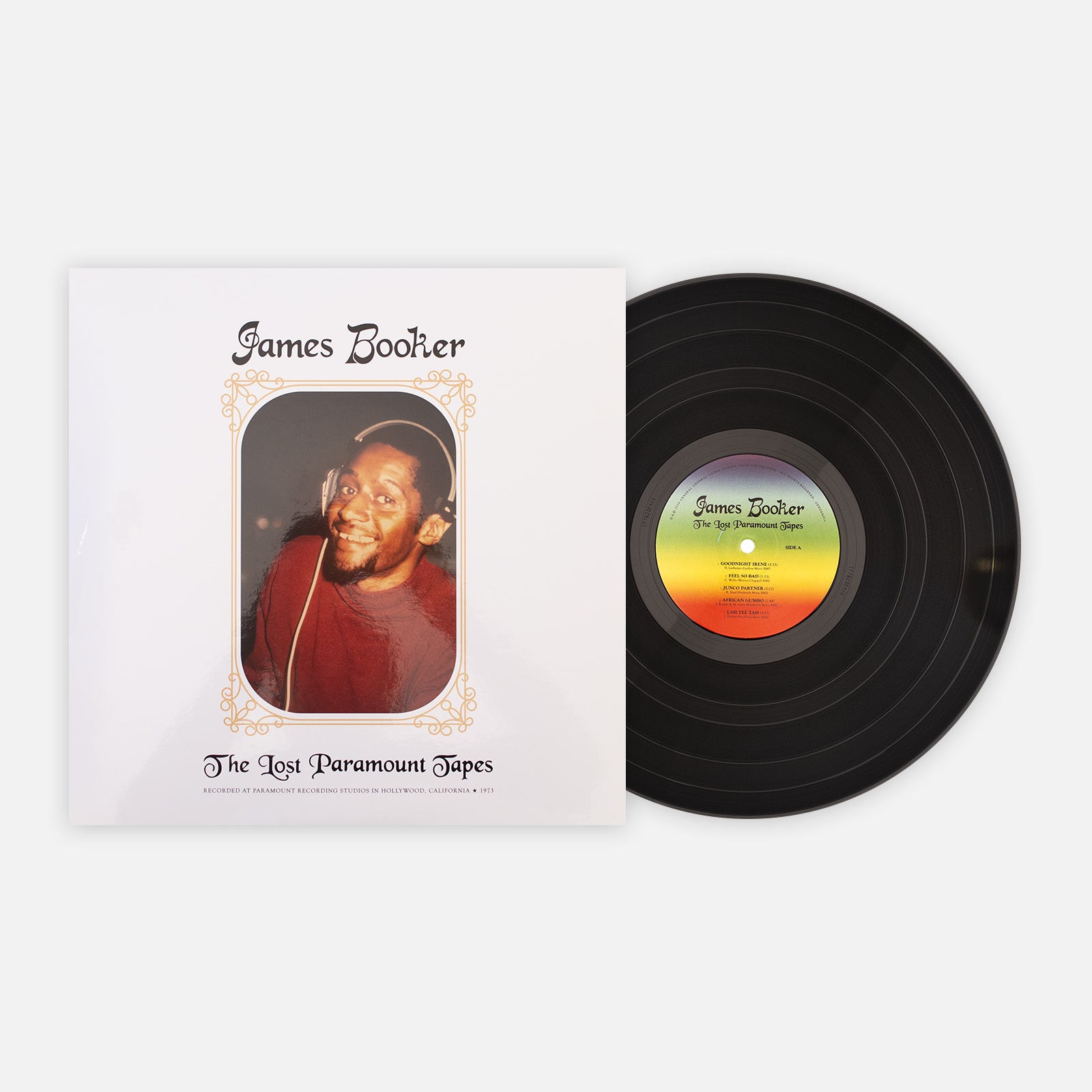

In August, members of Vinyl Me, Please Classics will receive the first-ever vinyl release of New Orleans jazz legend James Booker’s The Lost Paramount Tapes. Recorded in one night in Los Angeles, and thought to be lost forever, the tapes resurfaced in the mid-’90s, and are on vinyl for the first time here. You can can sign up here.

Here, we have an excerpt from the Listening Notes Booklet in our edition of the album, written by Lily Keber, who directed a documentary about Booker.

James Booker was one of America’s most stunning piano players. He was born, and died, in New Orleans, and in his 43 short years created an approach to the piano that has not been matched since. His music defies classification. It’s not exactly the blues, it’s not exactly jazz, it’s not R&B, it’s not classical; it’s a synthesis of all those. In a rare alignment of some forces that could never possibly be replicated, The Lost Paramount Tapes features James Booker leading a band comprised of New Orleans’ greatest underground monster musicians recording overnight in a studio after playing a gig. In Los Angeles. In 1973. And just to make this scenario even more bizarre, Booker is playing tack piano, which uses metal tacks to strike the piano strings instead of the usual hammers. Imagine the sound of a piano in a honky-tonk in the Wild West and you’ll get a pretty close approximation.

Then, after recording what could and probably should go down in history as one of New Orleans’ finest albums (though not recorded in New Orleans), Booker takes the masters, disappears for a while, shows up later in New Orleans minus both the master tapes and his right eye.

Welcome to the wild world of James Booker.

Here is what we know. James Carroll Booker III was born at Charity Hospital in New Orleans on December 17, 1939. He was born middle class, the son and grandson of Baptist preachers. After his father became ill during Booker’s early childhood, he and his sister Betty Jean were sent to live with an aunt in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, a small gulf coast town. He was a child prodigy on the piano. “I was burning boogie woogie up by the time I was 4 years old,” he remembered. “I learned all kind of ways. I played by ear and I played by music.”

At nine years old, Booker was hit by a speeding ambulance. The impact nearly killed him. He was treated with morphine to alleviate the pain in his broken legs. He credited the experience with morphine as “the first feeling of euphoria I ever experienced.” Booker struggled with addiction to heroin and alcohol for the rest of his life. He tells the story of the incident in his autobiographical tune, “Papa Was A Rascal.”

In 1953, Booker moved back to New Orleans permanently to live with his mother. He enrolled at Xavier Preparatory School, a well-respected Catholic high school. Booker was a gifted student and well-liked by his teachers, albeit a class clown of sorts. At 14, Booker performed blues and gospel on the radio over WMRY, while practicing Bach concertos in private. Producer Dave Bartholomew, a key figure in the transition of rhythm & blues to early rock ’n’ roll, was impressed enough with 15-year-old “Little Booker” to release the single “Doing the Hambone” on Imperial Records in 1954. Although “Hambone” and “You’re Near Me” on Chess Records failed to sell, Booker gained notoriety as a session musician in New Orleans. Recording engineer and studio owner Cosimo Matassa was confident enough in Booker’s chops that he boldly invited him to play Fats Domino’s piano parts on Fats’ own recordings. Before his 18th birthday, Booker had his mother sign papers to declare him an emancipated minor so he could pursue the musical opportunities coming his way.

After graduating high school in 1957, Booker went out on the road with the heavy hitters of the chitlin circuit, traveling with Joe Tex, Shirley & Lee and even posing as “Huey ‘Piano’ Smith,” a key influence on early rock ’n’ roll known for national hits such as “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu.” (Smith did not like to travel, and audiences in the late 1950s often did not know the faces of the voices they heard over the radio). Back in New Orleans, Booker played at the Dew Drop Inn, the premiere black nightclub, sharing the bill with Little Richard, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett and Duke Ellington as they all passed through.

Soul revues, like those at the Dew Drop in the 1950s, often featured exotic dancers and female impersonators, including New Orleans soul singer Bobby Marchan. Musicians like Little Richard assumed sexually ambiguous identities in their performances, and Booker got along famously with Little Richard. Booker’s childhood friend Charles Neville of the Neville Brothers describes the permissiveness of New Orleans at the time: “It was accepted… ‘That’s the way he is.’ Different strokes for different folks.”

In 1960, 21-year-old Booker recorded “Gonzo,” an instrumental featuring a playful, funky hook on the Hammond B3 organ released on Duke/Peacock Records. The song was his first Top 10 hit on the Billboard R&B charts and reached No. 43 on the pop charts. Hunter S. Thompson was infatuated with the song: His “Gonzo Journalism” style owes its name to James Booker.

In 1966 and 1967, Booker’s mother and sister passed away within six months of each other. Booker’s friends describe his profound grief from the rapid succession of tragedies and suggest he never really recovered. Perhaps as a reaction, he set off for Harlem in 1967. Booker went out on the road with Lloyd Price, recorded with B.B. King, Lionel Hampton and Aretha Franklin. Charles Neville remembers hanging out with Booker in New York outside of the sessions: “He’d get a cab and ride around and go to the dope places to score and hang out a while with the cab waiting.”

Booker returned to New Orleans in 1969. At the time, District Attorney James Garrison was leading an aggressive crackdown on gambling, drinking and prostitution. In 1970, Booker was arrested for possession of heroin outside of the Dew Drop and sentenced to two years hard labor at Angola, a former plantation and site of the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

In prison, Booker taught inmates to read. He taught himself to play Franz Liszt and Sergei Rachmaninoff. He played in the prison band “The Knicknacks” with Charles Neville of the Neville Brothers, Chris Kenner (“I Like It Like That”) and New Orleans funk drumming legend James Black. The Knicknacks must have been the greatest prison band ever assembled. In Charles Neville’s words: “…the Knicknacks could have competed with any band of that era — Cannonball Adderley, Horace Silver, Art Blakey, even Miles…”

Upon his release, Booker broke parole and set off for Los Angeles, where he joined a community of New Orleans ringers seeking refuge from Garrison. Booker worked on sessions and jammed with Ringo Starr, Maria Muldaur, T Bone Walker, Charles Brown, Jerry Garcia, Eric Clapton, the Doobie Brothers and even outlaw country singer Jimmy Rabbitt.

He called up his friend Dave Johnson, who he knew from touring with Dr. John. Dave was living in Los Angeles and told Booker he could stay with him. Dave helped Booker get established, taking him to gigs with him where he would get hired on spec.

Dave Johnson recalls: “I had contacted a friend of mine who managed a night club out in the San Fernando Valley called Dirty Pierre’s. And I said, ‘Hey, can we play your back room?’ It was a rock band on one side and there was kind of a little lounge on the other. Every once in a while he would put in a folk singer or something like that. And he says, ‘Sure, come on out and we’ll try it for a weekend. If it works then we’ll keep you going.’ So, we went out, had a piano put in there. And it was me and Booker and John Boudreaux. And so we set up and play and the kids in that club, they had just never seen anything like that in their life. So, we started playing there pretty much every Thursday, Friday, Saturday night.”

It was so rocking, in fact, that Johnson made plans with Daniel Moore of DJM Records to record the band. “I started contacting the other musicians I knew from when I played with Dr. John. Didimus on percussion, Alvin ‘Shine’ Robinson and David Lastie. And we all went into the studio on this one night at Paramount Records. We spent the whole night recording whatever Booker felt like recording.”

Though the choice of tack piano may seem bizarre, it was a conscious choice on Booker’s part. “Paramount Records in Los Angeles is right next to Studio Instrumentals on Santa Monica Boulevard. I went over and said, ‘Booker we can get any piano you want.’ And there’s a huge room of pianos: there’s grands, there’s nine-foot grands, baby grands. And he walks right up to this little spinet tack piano, sits down, starts playing. He goes, ‘Dave, this is the one.’ I go, ‘Really? Of all these pianos you want this little crappy piano?’ He goes, ‘Yep, that’s the one.’ So I said, ‘OK, move it over.’ So, we did the whole session on that piano and you can hear the results. It’s pretty amazing the sound that he got out it.”

You’ll feel that sound from the first chord drop, from Booker’s uptempo, swinging version of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene” to his originals. I defy you to find a funkier piano riff in the history of recorded music than the one Booker lays down on “Feel So Bad.” The layers of Afro-Caribbean-by-way-of-Louisiana percussion laid down by John Boudreaux and Didimus feature prominently throughout the album, alongside Shine’s playful vocal counterpoints and Dave Johnson’s solid bass spine. “Tico Tico” is a classic example of Booker taking a slightly dated, mostly cheesy song and completely reformatting it into a fresh and funky anthem.

Despite being packed with rollicking New Orleans greatness, the tapes never gained any traction at any label. Though no one could deny the level of musicianship, it wasn’t a sound that would move units. Johnson remembers: “We tried to shop it around and nobody really wanted it. We were looking for a record deal out of it and nobody wanted to spend the money. It really wasn’t, in Los Angeles, it wasn’t what they were looking for.”

This was a situation Booker would find himself in countless times. Everyone recognized the genius of his playing, but no one could find a way to translate that into record sales. And just as he was getting a handle on his chemical addiction, the rug was yanked out from under him.

Johnson tells the sad tale: “When Booker came out to Los Angeles, he assured me he was on this methadone program. Seven days a week, we’d have to drive from Burbank to UCLA in Westwood and he’d do his little shot of methadone. The times were great. He was getting his name around the L.A. music scene and getting a few calls for some things. And then all of a sudden, the methadone program stopped. They said, ‘Well, Mr. Booker you no longer have to be on this program. You’re all finished.’ And he goes, ‘What do you mean?’ They say, ‘You haven’t been drinking any methadone for the past two or three weeks. We’ve just been giving you Huperzine and Kool-Aid.’ Boy, that’s when the times changed. He got back to my place and just flipped out. He was so mentally hung up on putting something in his body and it was just a mess. I actually called them and said, ‘Look, you’ve got to let him back on the program.’ And they would not let him back on. They said, ‘Nope, he’s been clean. He’s done.’ So all of a sudden he was making phone calls down to his buddies in L.A. and saying, ‘Come help me.’

Booker’s behavior got so unpredictable that Johnson had to ask him to leave his apartment. When he left, he took the two-inch master tapes from these sessions with him. No one ever saw them again. The session faded from memory. Then in the mid-1990s, producer Daniel Moore got a call from Paramount Studios. They had sold the place and were clearing out their archive. They told Moore to come get his tapes. What Moore found was the two-track rough mixes from that night. Stuck on a shelf after the recording, they had sat untouched for two decades.

The Lost Paramount Tapes was first released in 1995, 12 years after Booker’s death. Johnson is the only musician from this album still alive. And yet the fierce power of this recording keeps it perennially vibrant. Put on your headphones, get in the right mental state and revel in this masterpiece.

Lily Keber is a filmmaker and educator in New Orleans. Her first film, Bayou Maharajah, chronicle the life and music of James Booker.