If there is any format that truly belongs to the vinyl era, it’s the double album. Holding the cover art in your hands is amazing as it is, but the experience which is so central to vinyl collecting is only upgraded by big gatefold sleeves opening up before your eyes. Not to mention four sides of music, each with their own beginning, arc and ending. The double album actually only makes sense when experienced on vinyl: in the CD age, when a single disc could contain up to 80 minutes of music, even regular albums seemed to become more filler and less killer. In the limitless era of streaming and digital downloading, the double albums perhaps makes the least sense of all.

That isn’t to say, however, that all double albums can be classified as such. The double album is a tricky thing, as many of them that are more adventurous than admirable prove. Simply stated: there are just too many double albums that didn’t need to be a double album. Artists who set out for an artistic highlight in their career and think the format can help them in achieving it, often fail and end up releasing overblown albums which would have been much closer to the intended masterpieces if changed to a comprehensive single album. These 10, however, do not suffer from that problem.

Bob Dylan: Blonde On Blonde

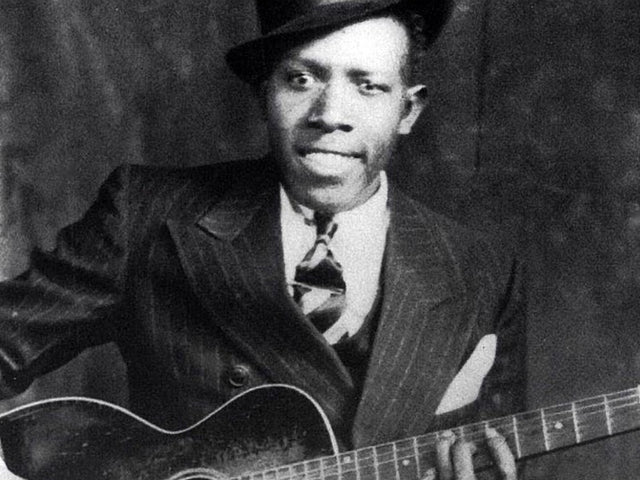

As with so many things in pop music, Bob Dylan is the one who brought the double album to the rock mainstream. There had been some relatively successful double albums in jazz before, but Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde brought the format into the spotlight in early 1966. Dylan, who was only 25 at the time, locked himself in a Nashville studio, where he worked with a multitude of session musicians. Blonde On Blonde became a symbol for the creative confidence of one of the greatest songwriters of all time, with Dylan usually making up his lyrics right on the spot. To this day, the double album sounds shimmering and marks one of the most exciting moments in Dylan’s extensive career.

Jimi Hendrix: Electric Ladyland

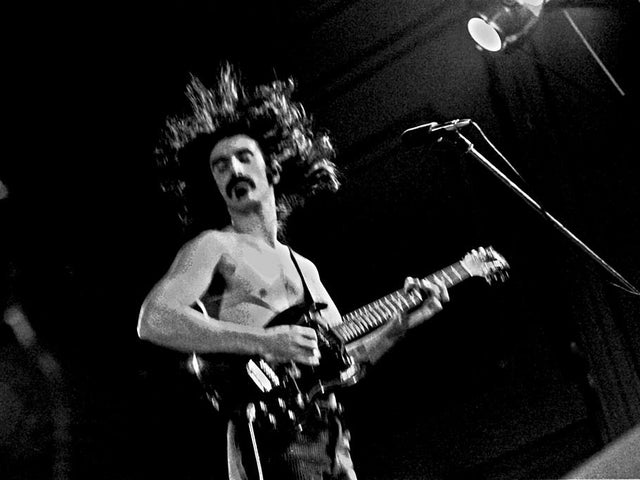

It didn’t take long for other rock giants to recognize the double album as an opportunity to explore and experiment. In the case of Jimi Hendrix, the subject of his fascination was, of course, the electric guitar. Like Dylan had done in Nashville, Hendrix, then 26, understood the studio as another instrument. The recording process of Electric Ladyland took place in the famed New York studio of the same name, where Hendrix himself produced this two-headed blues beast. Electric Ladyland, which runs for 75 minutes, features two versions of “Voodoo Chile,” one of which serves as the album closer and is preceded by “All Along The Watchtower” and “House Burning Down.”

The Beatles: The Beatles

It’s perhaps the world’s best known double album, and rightfully so. In 1968, The Beatles blew the world away as they seemed to summarize all sides of their musical personality in one project. The release in which it resulted, often called The White Album, has a bigger range than other bands’ entire discographies do. After much of the material had been written during meditation courses in India, arguments among the band members broke out while recording the album in London, with the omnipresence of John Lennon’s new partner Yoko Ono proving problematic. It seems only fitting then, that The Beatles is arguably the most divisive record in the Fab Four’s discography, with its postmodern lyrics conjuring up controversies and allegedly inspiring Charles Manson.

Miles Davis: Bitches Brew

Vinyl, and double albums specifically, allow music to breath. And there sure is a lot of breathing going here, on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. Hyperventilating, to be more precise. In 1970, the master trumpeter caused his own big bang, combining elements until they culminated in a radical rewriting of the jazz rulebook, bidding bebop farewell and embracing African music. Two bass guitars and three electric pianos ensured Davis disposed of a new palette to colour his compositions in with. One of those bass guitars was played by Harvey Brooks, who previously performed with Bob Dylan and seemed to symbolize Davis’ embrace of chord progressions associated with rock, making Bitches Brew one of the first albums to transcend genres and create new ones on its own terms.

The Who: Quadrophenia

There’s two kinds of double albums, roughly: double albums that provide artists with the space they want and double albums that provide artists with the space they need. The Who’s second rock opera surely falls into the latter category. After the commercial success of Who’s Next, a personal disappointment to Pete Townshend, the Who tread somewhat familiar waters with 1973’s Quadrophenia. The British band had already achieved acclaim with their earlier bizarre-but-brilliant rock opera Tommy. As radical as that release seemed, so (relatively) refined was Quadrophenia, an album unhindered by the success of a single like ‘Pinball Wizard’ and a project with simply too much story to tell for a single album. Townshend & co. tell the story of Jimmy, one of their first fans, set against the backdrop of the mod movement of the sixties these masters belonged to themselves. Thought the Who drew on their own roots here, the tale of a lonely boy looking for love in the city turned out to be as timeless as much of the music on Quadrophenia.

Led Zeppelin: Physical Graffiti

Double albums can allow artists to venture into previously unknown territories, but they also make it possible for them to perfect elements they’ve exercised earlier. In 1972, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page travelled to India together and were inspired by local studio musicians. The recordings they made laid the groundwork for the most extreme and eclectic album the normally relatively economical band ever released. here’s more adventure in the free-flowing “In My Time Of Dying” than there has ever been in another 11 minutes, and listening to “Kashmir” and “In the Light” proves once and for all that Led Zeppelin were, the heaviest band on the planet.

Stevie Wonder: Songs in the Key of Life

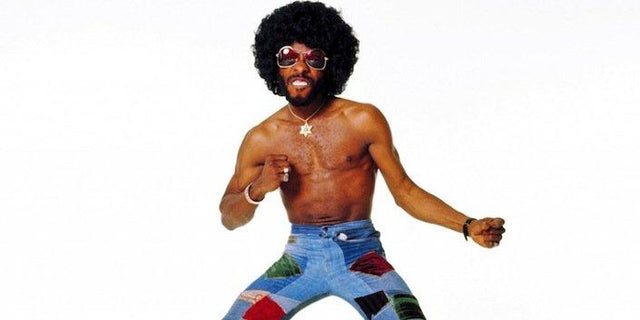

There’s a lot of Songs in the Key of Life, it turns out: this 1976 double album by Stevie Wonder clocks in close to two hours and every minute of it is as joyous as the last one. Here, Wonder gives way to an entirely different quality of the double album. The format is not only meant for serious conceptual cornucopias: it’s also meant for having fun and giving full vent to your multi-instrumentalism and musicality, like Wonder does on huge hits like “Sir Duke,” “I Wish” and “Isn’t She Lovely.” Songs in the Key of Life was Stevie’s eighteenth album, but the one of the most popular figures in R&B and pop music here sounds as enthusiastic as ever, like a kid in a candy store. That colourful image this album conjures up is only enriched by the knowledge that Wonder didn’t only dispose of synthesizer keyboards and saxophones, but also of a soulful all-star crew including Herbie Hancock, George Benson and Minnie Ripperton.

Pink Floyd: The Wall

The band who had dominated the decade released their final masterpiece in the last few weeks of the ‘70s. Fittingly, Pink Floyd’s The Wall used the opportunity to simultaneously reflect on Roger Waters’ unease with the band’s superstar status. The Wall then was almost entirely conceived by Waters, who also took inspiration from his father’s death during the Second World War, which the album starts with. In many ways, The Wall bids farewell to Pink Floyd, with the protagonist of the project being modelled after Waters and the band’s original frontman Syd Barrett and handling Waters sometimes self-imposed isolation from society. Songs like “Comfortably Numb” and “Another Brick in the Wall Part II” are as much hit singles as they are the sound of Pink Floyd falling apart. It makes for one of the most fascinating albums of the band’s career: they would go on to release three more albums, but never did so with the classic line-up and never managed to make another record that could even stand in the shadows of The Wall.

The Clash: London Calling

The Clash single handedly screamed social consciousness back into pop music with their menacing mixture of ska, reggae, R&B, punk and power pop. On London Calling, Joe Strummer and Mick Jones make a convincing case for the ownership of the label Last Angry Band, which is often assigned to them. The album, which followed on the Clash eponymous debut and Give ‘Em Enough Rope, in fact became a double album because of the energetic rate at which the two were writing their songs. It allowed the Brits to create a brutal album about individualism and isolation, as sharp of views as it was of tone.

Prince: 1999

Prince is perhaps the only musician ever to have released a double album without wanting to. In 1982, the Purple One was improvising a lot in his Minnesota home studio, recording songs as soon as the inspiration struck him. Among his work were dance tracks, beautiful ballads and rowdy rockers, which soon made up more material than one album could contain. “I didn’t want to do a double album, but I just kept writing and I’m not one for editing”, Prince told the Los Angeles Times later that year, when 1999 was released. The album became the artist’s breakthrough, featuring perhaps the most funky songs he’d ever release. When the original Blade Runner was released in the summer of 1982, Prince started incorporating the film’s futuristic styles and themes into the music. He surely succeeded: tracks like album opener “1999,” “Lady Cab Driver” and “Little Red Corvette” still sound like they could be released tomorrow.