Val Shively’s R&B Records Is The Best Record Store In Pennsylvania

The 50 Best Record Stores In America is an essay series where we attempt to find the best record store in every state. These aren’t necessarily the record stores with the best prices or the deepest selection; you can use Yelp for that. Each record store featured has a story that goes beyond what’s on its shelves; these stores have history, foster a sense of community and mean something to the people who frequent them.

Val Shively’s record store is a five-minute walk from the dingy 69th Street transportation center that introduces West Philadelphia to Upper Darby and sends buses and regional railways away from the city. When you walk out of the station, downtown Upper Darby looks like West Philly transplanted onto a small Main Street corridor. It also feels like a place in flux, both bleak and vibrantly diverse. On the row of blocks that leads to and around Shively’s business, there are storefronts like Uncle Mussa’s Grocery and Sanjha Bazaar, La Tienda Grocery and Soop Bin.

By design and in comparison, Shively’s front door hides in plain sight. You can’t see the painted “RECORDS” sign above the door if you’re right under it, and from across the street it looks worn and sad, like it may have belonged to a previous owner. On the glass door there’s a “Do Not Enter” sign with small print that reads “unless you know what you want” and a “5 Minutes and you’re gone!” menace to accompany it. Immediately inside, the door opens to a swarm of records everywhere but a narrow path forward. A fake skeleton is propped up on a counter and has a laminated sign taped to its torso that reads: “The last guy we caught stealing!!!” The Comic Sans font drives home the unintentional campiness of it all.

Like the house of a highly functioning hoarder, the inside of Val Shively’s R&B Records is not conducive to anybody besides its residents, Shively himself and Chuck Dabagian, his helper and store manager of four decades. Shively’s business card advertises “more than 4 million vinyl records,” an estimate that sounds snatched from the ether and quasi-legitimized by the quotation marks that surround it, like a slice spot that serves “the best pizza in New York City.” Whatever that many records looks like, Shively’s store at least threatens that so many could exist in one place. The effect is amplified by the fact that customers are generally not allowed to browse the bulk of the records for themselves, and also because most of the records are the small kind, which makes the prospect of fathoming their volume all the more daunting, and digging through them all the harder.

Shively has been obsessed with records since he was a kid. “I didn’t have girlfriends, I didn’t go to my prom or any of that shit,” he told me on a Saturday earlier this year at the messy counter that divides the public front of his store from the private back, where rows of enormous built-in shelves bow with 45s. “I just was in my own world and there was nobody else in it but me,” he said. By his late teens, Shively was hustling side-jobs to buy and sell records.

“The more you get into this, you go back,” he told me, explaining the origins of his obsession with 1950s and ’60s vocal harmony groups in particular — doo-wop — the genre that still defines his business. “I was fooling with the dial one day and I went, ‘What the hell is over here?’” In the early ’60s, as a teenager in the Philadelphia area, he’d turned his dial to the Camden deejay Jerry Blavat and the revelation recalibrated an already obsessive course. “Pre-’56 is a whole different black era,” he said. “It’s all black by the way, everything was black. All harmonies, but in the beginning it was completely different and then it grew into rock ’n’ roll. Before that it was rhythm and blues. Rock ’n’ roll has got a beat. It’s easy to like. The other shit, it’s like drinking scotch for the first time. You spit it out and say, ‘How could anybody have this shit?’ But you know what, you get used to it.”

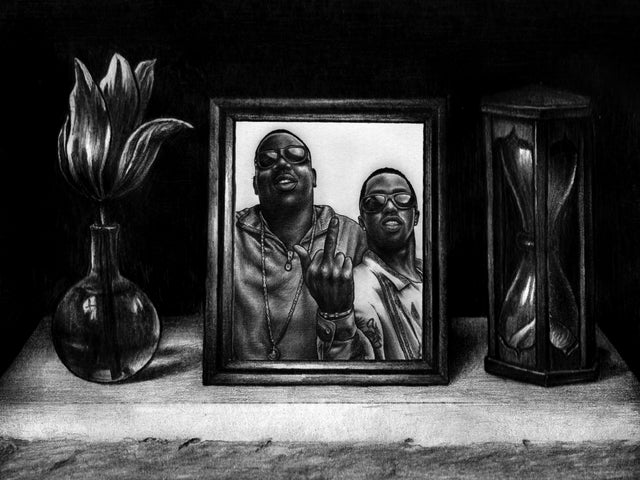

Photo by Jay Balfour

Photo by Jay Balfour

The urge to collect anything at all rewards obsession, and Shively has now spent a lifetime nursing his, amassing records and selling them off. Rolling Stone once crowned him the “Emperor of Oldies,” but it was a National Enquirer article in 1975 that put Shively’s store on the radar as a sort of center of gravity among collectors of rare vocal harmony group singles, first pressings or bust. The headline, “There’s Gold in ‘Golden Oldies,’” framed the picture of Shively holding a $1,000 doo-wop record. Back then and for much of his career, Shively’s business has functioned as a mail-order catalog of records. You have to go out of your way to spend a thousand dollars on a record.

Shively has moved shop a couple times since that National Enquirer write-up, but he’s been in the same three-story row building in Upper Darby for almost 30 years, and it shows. He remains an infamous and lively curmudgeon of a shopkeep, Dabagian by his side as the accommodating attendant behind the counter. Together they still run a mail-order business, which is how Shively likes to describe his store to new faces that walk in the door, not so gently nudging them to turn around and leave before they try to settle in. If you know what you want and they’re not too busy, Chuck will take your order — label, artist, song — and rifle around the back of the store to find it. Despite the sheer volume of records, Shively has a specialty and still trades most passionately in high-price oldies, but his store is overflowing with old R&B, soul and funk 45 singles of all types. Most of Shively’s stock is sourced from old jukebox suppliers, radio stations and deadstock from warehouse distributors. The effect is that of a database, Shively as its crazed benefactor, Dabagian as its librarian.

On my first visit to Shively’s I wedged myself in the front door and began exploring the records immediately inside. Once you’ve taken a step or two inside, if someone is in front of you, you need to backtrack toward a corner near the front door to let them out. The claustrophobic front is defined by a towering wall of CDs and a shelf of mixed bag LPs that require craning your neck sideways and deciphering the cat-scratched spines of lower shelves. The back of the store isn’t generally open to the public, so this small, narrow pathway is the only place to look for yourself.

Still, all of Shively’s shelves and piles have been picked at and pored over by famous collectors from around the world, and the prospect of so many records still retains the possibility of a hidden gem. But Shively knows what he has, and he still trades in specifics. I took the train to Val’s that first time to continue burrowing down a rabbit hole of completionism, seeking out records by the soul singer Leroy Hutson. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Curtis Mayfield groomed Hutson — who roomed with Donny Hathaway in college and wrote songs for Roberta Flack — as his replacement as the lead of the Impressions. After a couple albums, Hutson followed Mayfield’s footsteps and set out on his own, and throughout the ’70s and early ’80s he released a trove of gorgeous, upbeat funk and boogie records. I went to Val’s not only to round out my collection of Hutson 45s, but also to wonder after a specific single he released early in his career as part of the duo Sugar & Spice, the type of promise of a connection point that is so alluring when buying records, and exactly what Shively meant when he told me, “The more you get into this, you go back.” I asked Dabagian about the Sugar & Spice single and he asked what label it was released on. Within a few minutes he had it in his hands, and then in mine.

On a later visit, when Shively finally allowed me behind the counter to browse for myself, Dabagian showed me the tattered paper label of the Curtom section — everything is categorized by label first and artist second — and left me alone. I bought more Leroy Hutson records than I’d already bought from the same place, realizing that Val had doubles and triples of singles I’d never seen elsewhere before. I bought Curtis Mayfield 45s I didn’t know existed, like a dubious, plain label compilation released around the time of his solo turn in 1970 that, with slightly altered recordings of Impressions songs he wrote, reads like a songwriter’s demo right ahead of a breakout. Shively seemed tickled that I knew what I was after but entirely disinterested in the music itself, which is the only obvious point of connection for most people sharing an interest but not taste.

In this way, Val’s is generally not a place for browsing or contemplation, which makes it a bit of a paradox as a record store, one worth talking about but hard to recommend visiting, or at least maybe one to be framed as a challenge. Still, it has the alluring and tight-knit effect of a public secret, and Shively likes to hold court with old friends and customers behind his counter.

The same day I was there I heard him take a phone call from a regular customer in search of “a set of Holidays,” apparently referring to the Philadelphia record label from the late 1950s. He wanted the whole run if possible. Later, Val sized up a walk-in with a single question: “Do you care if they’re first pressings?”

Photo by Jay Balfour

Photo by Jay Balfour

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!