Brian Eno has made a remarkable stamp on popular music for a self-described non-musician. As a British art student, Eno attended a lecture by The Who’s Pete Townshend and realized his own creative capacity. Since his start as a member in Roxy Music, Brian Eno has been a prolific musician for nearly five decades. He has collaborated with pop stars, noise bands and avant-garde composers. Eno regularly releases solo albums, but he is seemingly just as content to collaborate with or produce for other artists. Though he has never become a household name, Eno has influenced so many strains of contemporary music that he is an icon to any music fan dedicated enough to dig through album credits.

Eno would likely prefer the title of theorist. The one constant through his forays into pop, rock, funk, ambient and electronic is a relentless intellectualism. Eno is consistently interested in the process as much as the result, constantly adding new variables to his recordings. His career closely resembles a successful visual artist: continuously working, experimenting with new media, learning from collaborators. With his range, Eno has become an ambassador for music itself. When Microsoft needed a six-second piece to sum up the possibilities of Windows 95, they asked Brian Eno. He made 84 different versions before deciding on the iconic startup sound.

The sheer number of Brian Eno records leads to wheat and chaff, but even his less remarkable albums contain stimulating thought experiments. His artistic peak coincided with the album era, and Eno took full advantage of the format to pursue all his musical ideas on wax. Whether he produces, writes or plays, here are the 10 best Brian Eno albums to own on vinyl.

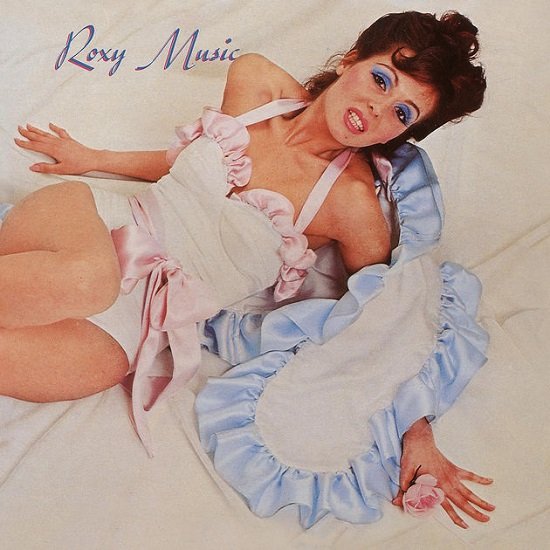

Roxy Music: Roxy Music

Eno made his recording debut as the synthesizer player and founding member of Roxy Music, a group led by preening frontman Bryan Ferry. Eno joined the group after encountering saxophonist Andy Mackay in a subway station, and true to his future behind-the-scenes work, he initially did not appear onstage during the group's performances. He first performed from backstage, operating a mixer, an analog synth, and singing backing vocals unseen, though he eventually joined in the glam makeup and costumes of the rest of the band.

The group's self-titled first album documents the post-hippie hangover through the lens of British art school alumni. The solo section of the first track, "Re-make/Re-model," is a collage of pop music detritus. After Ferry finishes singing about a beautiful woman he can identify only through her license plate, each member riffs on another song, from "Day Tripper" to "Ride of the Valkyries." The last 30 seconds of "Ladytron" are Eno's moment in the spotlight, a galloping rock beat giving way to a cavalcade coda of flanging pings and distortion. Roxy Music exists on vinyl in multiple versions, with edits following the departure of original bassist Graham Simpson and the addition of superb debut single "Virginia Plain." In any incarnation, it's an excellent introduction to a legendary art rock outfit and to Eno's lengthy musical career.

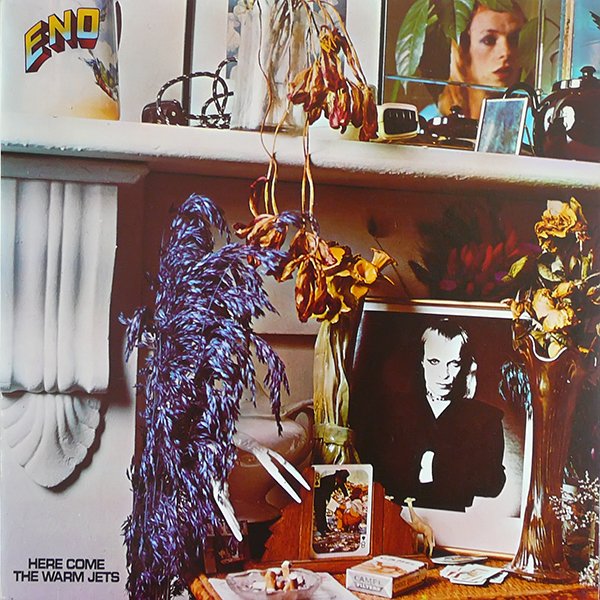

Eno: Here Come The Warm Jets

Tired of disagreements with Ferry and the burgeoning rock band lifestyle, Eno left Roxy Music after their second album. He launched a solo career immediately, still enigmatically credited by solely his surname. For his solo debut, Here Come The Warm Jets, Eno assembled a wide range of musicians based on his hope that they would be incompatible together. As he put it, the sessions were "organized with the knowledge that there might be accidents, accidents which will be more interesting than what I had intended."

The resulting record is captivating, haphazard glam rock with an undercurrent of menace. The guitars on "Needles In The Camel's Eye" bash out major chords with such force it seems the strings might snap, until the music thrillingly cuts out for a measure mid-solo. Eno wrote his vocal melodies as nonsense syllables over the instrumentation first, then transcribed the phonemes into free-associative lyrics. "The Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch" opens with "My my my, we're treating each other just like strangers," an evocative hint at a personal relationship, that reveals itself to be about the A.W. Underwood, historical figure and rumored pyrokinetic. Eno croons "Given the chance, I'll die like a baby" in "On Some Faraway Beach." The juxtaposition of tranquil death and a child is haunting, but the underlying piano is comforting. Eno explained that the title of this album referred to guitar tone like a "tuned jet." Beginning with his debut, Eno was taking off from rock music entirely.

Brian Eno: Ambient 1: Music For Airports

Few artists can claim the invention of an entire genre, but if Brian Eno didn't create ambient music, he certainly gave it a title with 1978's Ambient 1: Music For Airports. True to that second clause, Eno conceived this album as a loop meant to be played on repeat in airport terminals. After suffering through a layover in a German airport besieged by annoying background music, Eno made a more suitable replacement, music "intended to induce calm and a place to think" according to the liner notes. It's more like a sound art installation than a traditional album, each of the four tracks like panels in a large painting. Tracks "1/2" and "2/1" are hypnotic loops of four vocalists, including Eno himself. Each vocal part is a different length, so the looping allows new harmonies to emerge like milk poured into black coffee. "2/2" was recorded on an ARP 2600 synthesizer, and it sounds like Vangelis' elegiac Blade Runner score compressed into six minutes. Opener "1/1" is the longest at over 17 minutes, but it's so soothing that the time passes quickly. The interlocking piano lines were sourced from a session with musicians who couldn't hear each others' playing. Eno chopped out a chance segment of union, played it at half speed, then layered in atmospheric synths at certain moments. In our "lo-fi chill beats to study/chill/relax to" era, where music is so ubiquitous that it can fade into the background, Music For Airports and the rest of Eno's ambient work are a testament to music's atmospheric power.

Talking Heads: Remain In Light

Eno first produced the New York quartet on their second album More Songs About Buildings & Food, still firmly in their post-CBGB guitar rock phase. On Remain In Light, he took them to the very brink of rock music. Initially hesitant to return as producer, Eno was impressed by the instrumental demos the group recorded in Nassau. The finished album arose from those demos, swelling from loops, polyrhythms and extra instrumentation. The first track "Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On)" is a mission statement. Layers of percussion shimmer over guitar scratches, minor chord melodies, and Tina Weymouth's punishing slap bass. Drummer Chris Frantz, fresh from performing on Kurtis Blow's "The Breaks," brought the same hip-hop backbeat to "Crosseyed and Painless." The lush songs include contributions from Adrian Belew's guitar, Nona Hendryx's voice, and Jon Hassell's horns.

Eno, earning his co-writer credit, is everywhere, playing bass, keyboards and percussion. Thought experiments flourished. Eerie closer "The Overload" was the group's version of Joy Division, a band they had read about but never heard. Byrne's free-associative lyrics were influenced by speakers across the radio dial: commercials, newscasters, preachers, rappers, talk show hosts. "Once In A Lifetime" is an American hymn to mid-life crisis. “You may say to yourself, ‘How did I get I here?’” Byrne gasps. Aided by Byrne's captivating performance in the video, it became their biggest hit. After releasing four albums in four years, Talking Heads took a three year hiatus, returning with the self-produced Speaking In Tongues. They never worked with Eno as a group again. Remain In Light represents their peak, a genre-free celebration of modern anxiety.

David Bowie: Low

As David Bowie recovered from cocaine addiction in Berlin, he stumbled upon Eno's 1975 minimalist work Discreet Music, a precursor to his ambient series. Impressed, the strung-out superstar summoned Eno to work on sessions for Iggy Pop's The Idiot and what eventually became Low. The record marked the first part of what was retroactively dubbed the Berlin trilogy, three albums where Bowie abandoned his previous narrative tendencies in favor of more abstract perspectives. The music shifted with the lyrics, from guitar-focused glam rock to enigmatic synth compositions.

Though Low was produced by Bowie and his long-time partner Tony Visconti, Eno is often erroneously credited as producer due to his outsize influence. In reality, Eno was like a patron saint, as if Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie had enlisted Little Richard in the studio. He lent his talents as a composer, experimentalist and synthesizer wrangler, particularly on the second side's mostly instrumental songs. "Warzsawa," the centerpiece of the album that opens side two, is based around a theme supplied by Visconti's four-year-old son, hammering out the notes A, B, C incessantly. Fertilized with Eno's layers of synths and Bowie's multi-tracked phonetic Polish, that seed sprouted into a masterpiece of longing. Low was a shift in Bowie's art that reverberated four decades on, from Heroes all the way through to Blackstar.

*Devo: Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!](https://amzn.to/2IvJP8C)

Akron's finest likely attracted Eno's eye thanks to their central concept. The name Devo stems from "de-volution," a half-satirical idea developed by Kent State undergrads. Shocked by the police brutality on campus in 1970, the art project became a band. Evoking a dystopia of regression to the herd mentality, Devo first gained notoriety when their music starred in an award-winning student film. David Bowie and Iggy Pop praised the group to executives, but Eno paid for their flights and studio time in Germany before they even signed a deal.

The jittery songs are pure id. "Too Much Paranoias" is less than two minutes of pre-hardcore stomp, interrupted in the middle by what sounds like a literal breakdown. Mark Mothersbaugh's wails are lifted from Burger King and the Sex Pistols. The Devo version of "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" sucks out all of Jagger's swagger, leaving only the self-obsessed core. Keef's legendary riff is replaced with dub bass and the percussion sounds of a factory. The sessions were reportedly tense, due to Devo's refusal to experiment beyond the scope of their homemade demos. The group was dedicated to their idea of de-volution, but they led plenty of new wavers down into the primordial ooze with them.

Eno: Another Green World

The young Brit packed a lot of work into the three years after his debut, a pace that rarely slowed through his career. Another Green World is the midway point between his early rock focus and his later ambient work. It opens with the acrid groove "Sky Saw." Strings on basses, guitars and violas scrape against each other as Phil Collins gets flashy. The bulk of the record is far more sedate. It feels like modern bedroom pop, Eno singing to himself about the passage of time on "Golden Hours."

Less than half of the songs have any lyrics. Despite the captivating instrumentals, the ear naturally latches onto Eno's vocals, clinging like a swimmer to a raft. With Eno's oblique writing method, there was no hope in floating on concrete meaning, but the water's fine anyway. Another Green World is not as momentous as Eno's other solo work, but it is an excellent summary of all his strengths.

Coldplay: Viva La Vida Or Death And All Of His Friends

Before conscious uncoupling and collaborating with the Chainsmokers, the British pop-rock quartet tapped Brian Eno to produce their fourth record. Likely inspired by his work with their arena-dominating forebears U2, Coldplay use Eno's co-sign to indulge in the excesses of the bygone art-rock album era. They expand from their traditional middle-of-the-road instrumentation and feature strings, synths, and ambient sounds. The first track "Life In Technicolor" opens with iridescent chimes from a yangqin, a Chinese dulcimer.

True to his own habits, Eno reportedly influenced the band's process as well. The producer encouraged them to travel through Spain and record in cathedrals, sometimes joining in on backing vocals huddled around a single mic. On "Yes," frontman Chris Martin abandoned his famous falsetto for his lowest register on record, a suggestion by Eno inspired by Lou Reed. The resulting track is a breakbeat under hypnotic strings, a rare Coldplay song with an edge. Viva La Vida even embraces some of the curatorial quirks of the vinyl era. "42" abruptly transitions from a Lennon-meets-Burton piano tune into a lean new wave shredder. "Yes" leads into the propulsive yet unlisted "Chinese Sleep Chant." In the lead-up to the album's release, Coldplay's ambition was unmistakable. The group wore knockoff Sgt. Pepper's uniforms and talked about the French Revolution, to say nothing of hiring a legend like Eno. For all their striving, they succeeded with Viva La Vida. Ten years on it's still the group's most cohesive and rewarding work.

Brian Eno & David Byrne: My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts

David Byrne and Eno recorded My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts before rejoining Talking Heads for the Remain In Light sessions, though it was not released until 1981. Its menagerie of samples required legal taming. Assisted by a cast of session musicians, the duo built pop grooves. The lead vocals came from samples, singers, speakers and preachers plucked from American airwaves. Eno and Byrne's analog trial and error required live playback of physical tape. "Help Me Somebody" brings Reverend Paul Morton and country guitars to the disco. "The Jezebel Spirit" layers audio of an exorcism over slap bass and cop show percussion. It sounds like Paradise Garage on Halloween. Depending on the edition, the record omits "Qu'ran," featuring audio of Qu'ranic recital, at the request the Islamic Council of Great Britain. The musicians amicably acquiesced, and the album does not unduly suffer without it. It is an experimental album that's less influential than simply lucky, but Life is great pop-funk that vibes with the rest of Byrne and Eno's work.

U2: The Joshua Tree

Hot off their star-making performance at Live Aid in 1985, U2 set out to mine an album from the deep valley between the mythical America and the actual Reagan-era nation they traversed on tour. Eno joined Canadian producer Daniel Lanois to bring this Irish quartet's vision of America to life. The British producer found a kindred spirit of sonic experimentation in The Edge. The guitarist plays a symphony of guitar delay and loops on the iconic opening of "Where The Streets Have No Name." On "Bullet The Blue Sky," he updates the chaos of Hendrix's national anthem for Iran-Contra, embodying the fury of American fighter planes and the paranoia of someone living helpless underneath them.

Bono's lyrics, perfectly balanced between universal and personal, anchor the album in the earth. There's the calm desperation of "Running To Stand Still," the dirt road infatuation of "Trip Through Your Wires," the convenience store gospel of "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For." Anyone who's flipped on the radio in the past three decades knows this album. Like Thriller or Saturday Night Fever, this album could practically be a greatest hits, but instead will have to settle for the distinction of being the best single record the group ever released.

Jack Riedy is a Chicago-based writer, comedian, and person. He is also the self-appointed world’s biggest Space Jam fan. Read more of his work at jackriedy.com.

Related Articles

Join the Club!

Join Now, Starting at $44Exclusive 15% Off for Teachers, Students, Military members, Healthcare professionals & First Responders - Get Verified!